Standing one hundred yards in front of the crossroads which formed the centre of Wellington’s line, it was obvious that the possession of the farm complex of La Haye Sainte gave complete control of this vital road junction. In French hands it would be an ideal launch site for a concerted drive along the Brussels chaussee and by capturing the Mont St. Jean complex would literally split Wellington’s force into two disconnected wings and allow his position to be rolled up. Defeat would be the inevitable consequence.

Realising its significance in the defence of his position along the crest, Wellington ordered the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion of the King’s German Legion to garrison the farm complex the evening before the battle. The Duke had confidence in their very experienced battalion commander Major George Baring and his near four hundred German troops who had shown their mettle on numerous occasions in the Peninsula.

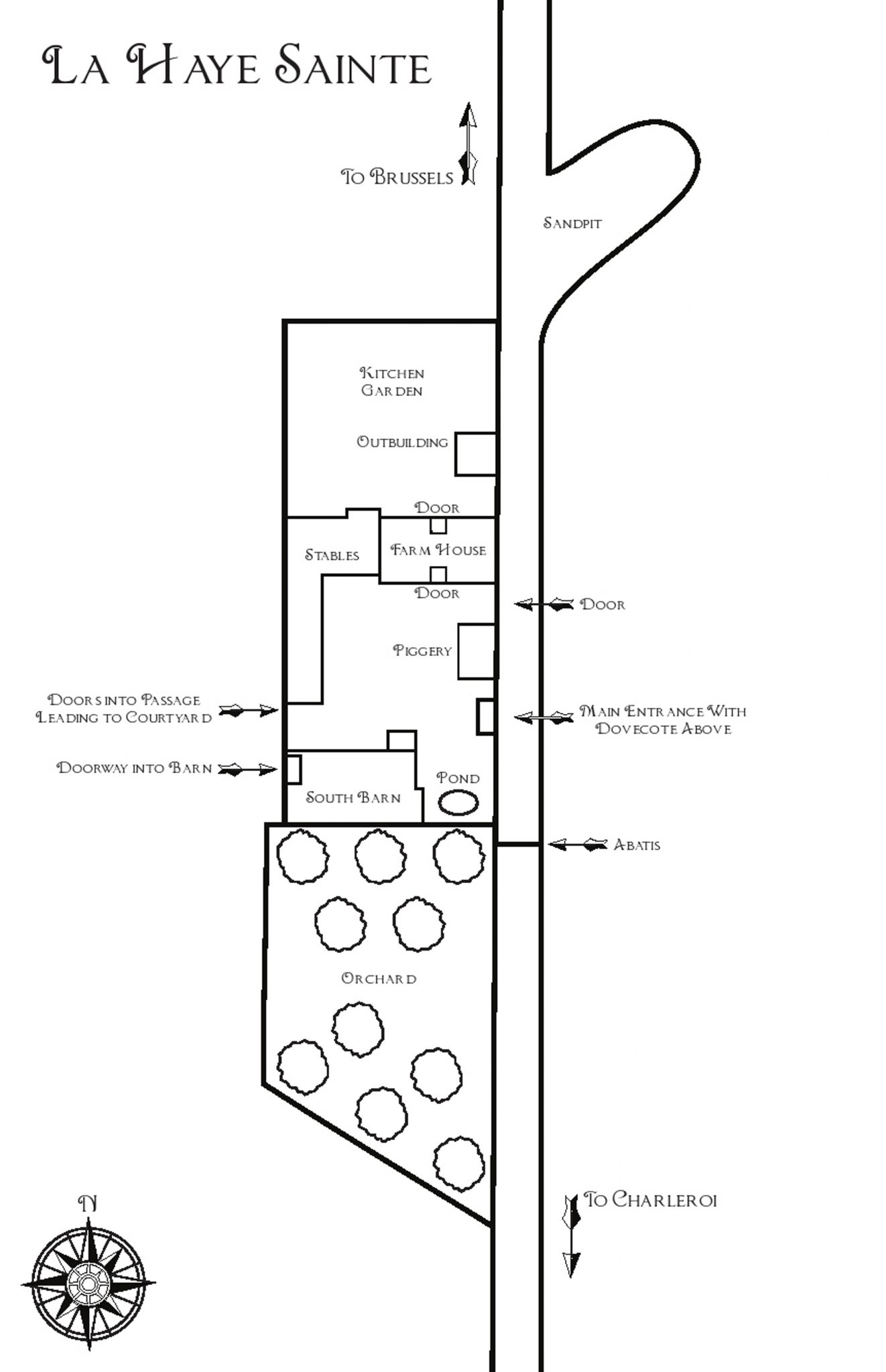

The farm of La Haye Sainte which runs alongside the western edge of the Brussels chaussee, it looked very much as it does today consisting of a farmhouse, barn and various stables and outbuildings, all connected by a high stone wall to form a very defensible rectangular structure, enclosing a spacious farmyard. Facing the French was an extensive orchard running south some 200 metres from the farm and to the north there was a smaller hedge lined vegetable garden extending 60 metres to the north. Access from the chaussee was via a gateway with a pair of large wood panelled doors, all topped by a dovecot; on the opposite side two large entrances with wooden doors allowed agricultural carts access to the farmland beyond, one directly from the yard through an archway in the stable block, the other through a large barn. Another small door in the wall near the farmhouse allowed pedestrian access onto the chaussee and access to the rear garden was via a passageway through the farmhouse. There was also a door by the pond into the orchard. All of the windows in the farmhouse were also barred, aiding its defence materially.

On arrival at the farm that evening at around 7:30 and despite the incessant rain and gathering gloom, Major Baring immediately ordered his men to prepare the farm complex for defence, but, the fact that he was to defend the farm the next day was clearly understood, for as he readily states, that with night ‘we…laid down in expectation of an attack the next morning.’

The men were roused before dawn and were soon set to continuing their defensive preparations. Building his defences was severely hampered by the loss of his pioneers – who had apparently been sent off the previous evening to Hougoumont to prepare that complex for defence – and the lack of any other suitable tools apart from the few found lying in the farm buildings. The situation was further complicated by the discovery that the barn door, giving access to the fields, had been removed, presumably by soldiers attempting to light a fire to warm themselves in the dreadful conditions. However, this opening was obstructed with farm implements to the best of their ability, the gates were all barricaded, firing steps were prepared and loopholes dug out with their bayonets. An obstruction (or abatis) was also formed on the chaussee from farm machinery, timber and any other materials found to hand, and was initially manned by part of the garrison.

The defences completed to the best of their means and abilities, the men took time to breakfast on whatever scraps they were fortunate enough to have preserved in their haversacks or discovered when scavenging through the farm. They religiously cleaned and prepared their weapons for action; each man of the battalion being armed with a Baker rifle, a sword bayonet attachment and sixty rounds of ammunition. Unfortunately, it would seem that no one thought to establish a further reserve of rifle ammunition before the action commenced; being so far in advance of the main line, resupply would prove incredibly difficult once the action had begun.

Baring had only the four hundred men in six companies of the 2nd Light Battalion King’s German Legion available and initially he placed three companies in the orchard, two in the farm and the other one in the rear kitchen garden.

When the battle commenced with the attack upon Hougoumont, the garrison of La Haye Sainte was not disturbed much, but for the numerous cannon balls flying overhead as they sought to destroy Wellington’s artillery and the few units visible on the crest. Skirmishers surreptitiously approached the orchard only to be thrown back by the heavy and extremely accurate cross fire from both Baring’s men and the 95th Rifles stationed in the sand pit across the chaussee.

This uneasy standoff ended with the advance of the entire French 1st Corps under d’Erlon against Wellington’s left wing, which commenced around 2 p.m. As part of this massive assault, the 1st Brigade of infantry of Baron Quiot’s Division commanded by Colonel Charlet marched directly upon La Haye Sainte. This brigade of just over two thousand men of the 54th and 55th Ligne Regiments deployed a thick cloud of skirmishers before them and marched directly for the orchard.

The heavy fire of Baring’s men decimated the skirmishers, but although the Baker rifle was vastly more accurate than a musket, it also was much slower to load. Soon the dark masses of the approaching columns were emerging from the smoke and despite a valiant defence, two hundred men in an open orchard could not hope to hold back two thousand for very long. Having suffered a number of casualties, and having been pushed back to the north end of the orchard, Baring was on the point of ordering his men to retreat when he was momentarily encouraged to continue fighting by the arrival of the Luneburg Field Battalion which had been ordered down from the ridge to support him against this infantry attack. Lieutenant Colonel von Klencke had led his men two hundred metres down the slope into the fray in line formation, ready to engage the French columns; but unbeknownst to him, Charlet’s flank was supported by Dubois’ Cuirassier Brigade of 1st and 4th Cuirassier Regiments. Nearly eight hundred Cuirassiers struggled to keep their horses in formation as their hooves sunk into the soft loam on the slow incline. They had been hidden by the undulations of the ground and the smoke of the batteries and as these heavy cavalrymen crested another low rise they saw the Luneburg battalion only two hundred metres away to their right front, moving against Charlet’s men in line and completely at their mercy.

The bugles sounded the charge and the 1st Cuirassiers set off at the quickest pace they could manage in the boggy soil, crashing into the flank of the flimsy line and rolling up the battalion in moments. The Cuirassiers stabbed away without mercy, scattering the Luneburgers and Baring’s men to the wind. A few of his men found their way into the farm with Baring, probably through the gate near the pond, but most sought to retire to the main ridge. But as they sought to scamper up the muddy slope, many a man was caught by the Cuirassiers, to die by a sharp stab in the back. Some would turn to fight, for the cuirass was no protection to musket balls fired at such close range and bayonets were lunged at horse or rider in a desperate defence, but many still fell to the point of a Cuirassier’s sword. A number were lucky enough to reach the protection of the squares of infantry which had formed up on the ridge, many more survived by feigning death as the horsemen rode on by only to become prisoners. But the consequence was that the Luneburg Battalion ceased to be a coherent fighting unit for the remainder of the day.

Charlet’s troops scented victory in their assault of the farm and their columns rushed against the walls on both the east and west sides. Axes and musket butts struck the door panels in an attempt to break in, but the French infantry were under heavy fire from the defenders who only bobbed into view for an instant to fire before retiring into the safety of cover behind the wall again to reload, giving few clear opportunities to retaliate. Fired upon from the walls, through the door panels or from the loopholes in the walls, almost every shot struck home; in fact it was not uncommon for a rifle ball to pass through two or three bodies in the dense crowd that surged up to the gates.

The wounded were often smothered and trampled underfoot as the French continued to desperately seek an entrance. Rifle barrels were grabbed in desperation as the defenders poked them out to fire but they usually soon released their grip having received a bayonet thrust from another defender. A number attempted to force their way past the obstruction built in the entrance to the barn where the gate had been removed and burnt, but a heavy fire from the defenders manning the opposite gate at the far end of the barn brought down every man that entered. Soon there was a wall of dead and wounded Frenchmen across the entrance further impeding and discouraging those that followed. Such intense fighting could not continue for long and beyond the farm d’Erlon’s great assault had been turned back, so Charlet’s men retired to the safety of their own lines with the rest of their corps. Some of these men were caught by the allied cavalry and it is possible that the 55th Ligne may have temporarily lost their eagle, although it was soon recaptured.

Baring now had a lull of some half an hour or so to shore up his defences and prepare for the further attacks which were sure to come. He sent messages to the rear, calling for a resupply of rifle ammunition as his men were starting to run short. His garrison was then supplemented by the arrival of two companies of 1st Light Battalion K.G.L. numbering some 180 men, these were placed in the rear garden and Baring’s men all filed into the farm complex. A short time later the light company of the 5th Line K.G.L. was also sent into the farm, but worryingly, no rifle ammunition arrived.

Realising the importance of gaining possession of the farmhouse, at about 3 p.m. Marshal Ney launched a second attack, but this time it was not linked to a large scale infantry assault on the ridge line beyond, allowing the defenders to concentrate all of their firepower upon the attacking battalions.

It was Charlet’s troops who were picked to assault the farm once again in an attack which largely mirrored the earlier one. The French troops massed at the main gateway on the chaussee, pressing against it and striking the gates with musket butts in a desperate attempt to break in, but constantly suffering from a deadly crossfire from the defenders and from the 95th Rifles in the nearby sandpit, the French were forced to retreat again having suffered huge losses. This attack was also repulsed by a desperate sortie by some of the defenders with bayonets. As Rifleman Lindau recalls

I went to a loophole next to the locked gate that faced the highway. Here, the French were so tightly packed that I often saw three to four enemies felled by a single bullet.

A short time later, our Captain Graeme had the gate opened, and we stormed with levelled bayonets against the tightly packed enemy. He did not resist because we pushed ahead with irresistible fury. I stabbed and hit into that mass like a blind man in a rage.

On the west side, further attempts were made to storm the open gateway into the barn, but they simply added further depth to the mound of bodies in the entrance and eventually the French attacks slackened. The French infantry stubbornly fought on, but having virtually surrounded the building, they still could not force an entrance. Eventually around 5 p.m. heavy losses and exhaustion compelled the French to retire and reform.

Baring again used this lull to shore up the defences and to send further urgent requests for rifle ammunition (British musket ammunition was too large to fit the rifle). No rifle ammunition arrived,but further reinforcements did arrive in the shape of about two hundred men of the light and at least one centre company of 1st Battalion 2nd Nassau Regiment who had previously been in Hougoumont wood, being part of Major Büsgen’s command.

Their arrival was fortuitous, for the French now attempted to set the barn alight. Luckily the barn had largely been stripped of straw by foraging troops the previous evening but the flames did start to take hold in the roof space. Major Baring tore a large camp kettle from the backpack of a Nassau soldier and ordered the troops to use them to douse the flames by filling the kettles from the pond in the corner of the yard which had been filled by the heavy rains of the previous night. Many a brave man fell in the act of attempting to extinguish the flames, but they were eventually successful and disaster was averted.

Another plea for ammunition was sent as his men were now down to three or four rounds per man and they had to search the dead and wounded for spare cartridges. They also sought to bolster their defences by filling up the shot holes in the walls caused by cannon fire. However, both Baring and his men knew that without help they would not be able to hold on much longer, but they had no intention of giving up without a fight. As Baring himself said later:

The contest in the farm had continued with undiminished violence, but nothing could shake the courage of our men, who, following the example of their officers, laughingly defied danger. Nothing could inspire more courage or confidence than such conduct. These are the moments when we learn how to feel what one soldier is to another – what the word ‘comrade’ really means…

Just before 6 p.m. Ney ordered another assault with a number of fresher troops. This time Charlet’s men were replaced by the three battalions of the 13th Legere Regiment (1,800 men) commanded by Colonel Gougeon and a company of engineers, supported by the 17th Ligne Regiment.

The 13th Legere concentrated their attack on the west side of the farm and they did successfully break through the door which led through the passageway in the stable block, only to be mown down by firing from a barrier quickly built at the other end of the passageway. Frustrated in their attempts to force their way in here and into the adjacent barn, they tried to set the barn alight again, but were foiled. However, some more intrepid souls were lifted onto the roofs by their colleagues and these Frenchmen were able to fire down from here at the defenders in the farmyard below with relative impunity as their ammunition supply finally began to run out.

At the same time Lieutenant Vieux with his engineers succeeded in bursting through the main gate fronting the chaussee. With both gates breached and with the defenders virtually out of ammunition, Baring ordered his men to retire through the farmhouse, into the rear garden, still held by the companies of the 1st Light Battalion K.G.L., and on up to the ridge.

Realising that the farm was in grave danger of being captured, the Prince of Orange ordered the men of the 5th and 8th Line Battalions K.G.L. to form line and to advance to drive the French away from La Haye Sainte. The two battalions advanced down the slope towards the unprotected flank of the 13th Legere, when all at once the line was struck in the flank by French Cuirassiers who had approached unseen once again.

The 8th Line was struck first and suffered very high casualties as they were simply rode over by the heavy horses and even temporarily lost their Colours as the remnants of the battalion simply fled back to the ridge. The 5th Line had a luckier escape as it just had time to form square because the French horsemen were struck in flank by the remnants of the Life Guards and Horse Guards and were chased away. The 8th Line Battalion lost its King’s Colour when Ensign Moreau was struck by three musket balls and Sergeant Stuart caught it, only to have his right hand almost severed by a Cuirassier, who then rode off triumphantly with the Colour. However, the 8th Line Battalion was fortunate to avoid the ignominy of losing their colours to the French for long, as they were found and returned to the battalion after the battle by Sergeant George Stöckmann of 2nd Light Battalion K.G.L. The 8th Battalion was so badly mauled by the Cuirassiers that having reformed square behind the ridge, they were unable to deploy again throughout the battle.

The great majority of Baring’s men who were still capable of fighting managed to retire through the farmhouse, before the French – who still had to negotiate the barricades under desultory fire from those Germans still fortunate to have a few cartridges left – could catch them.

Many of the French troops, elated by victory, desperate for plunder and full of vengeance for the losses they had sustained by the stout defence of the Germans initially gave no quarter to any unlucky defenders they discovered still alive. But not all had lost their humanity, and a number of the defenders were rounded up and driven to the rear as prisoners, plundered of anything remotely valuable or useful.

The farmhouse had fallen and the defenders had fled back to the ridge where the majority returned to their parent units and the remnants of Baring’s battalion formed up alongside the 1st Line Battalion K.G.L. in the sunken roadway.

In a final desperate attempt to prevent the French exploiting their success, an order was sent from the Prince of Orange – or at least on his authority – for Colonel Ompteda to reform the men of his 5th Line Battalion into line and to drive the French infantry away from La Haye Sainte. Initially he refused on the grounds that the Cuirassiers who had struck so devastatingly twice earlier were still just visible in the little hollow they had previously attacked from. But having received a peremptory order to do as he was commanded, Ompteda handed his son over to a trusted colleague and led his battalion forward into an obvious death trap. As predicted, just as the 5th Battalion reached the hedge of the kitchen garden, the Cuirassiers struck and the battalion was duly cut to pieces. Only a flank charge by the 3rd Hussars K.G.L. saved the battalion from complete annihilation. Poor Ompteda was last seen still on horseback near the hedge of the kitchen garden, fighting off the attacks from several infantrymen, only to eventually slump to the ground dead, having been shot through the neck.

The French had finally gained complete control of La Haye Sainte and the centre of Wellington’s line was close to collapse. In an attempt to shore up the centre, the 27th Inniskillings had been placed in square just behind the crossroads where they took the brunt of the French fire as they sought to break through; the regiment literally died in square, losing 478 killed and wounded from a total of 698 men present (68%).