Extract from Gareth Glover’s Waterloo Archive 2

Towards evening we marched through a field of high corn that we trampled into the mud, making it look as if it had been mown, and then arrived at the farmstead of La Haye Sainte, which borders directly on the highway. Two companies were immediately sent into the orchard, which did not please me at all because I could not find a single dry spot. I therefore went into the courtyard in a search for some straw; here I met my brother who was unable to give me any, either, as there was nothing left in the barns.

It was then that Major Baring came out of the house and gave an order to butcher the livestock that was still left in the stables. The meat was distributed, and also to the men of the line battalions outside who had shown up to find some straw. In the meantime, I had discovered some peas in the loft of the house, which I gathered in a cloth; with these and a large piece of meat I hurried back to my comrades and asked them to light a fire. Since it was still raining and the ground in the garden was just mud, nobody was in the mood. One of them was leaning against a tree, another against a wall; others again had sat down on their knapsack and were staring at nothing in particular; nobody was willing to lay down.

I therefore went back to the courtyard where I had heard that there still was wine in the cellar. I sneaked in there, found a cask that was half full and filled my canteen. With this I went on a search for my youngest brother who I knew was with a battery nearby. He was the one that at Rohrsen had been chased back [home] with a good beating from me; we had not seen each other again since that time.

In front of the gate of the barn I happened to bump into men from our 1st Battalion; they almost emptied my canteen. I then went off in the darkness and was soon challenged by a patrol. The corporal who led the patrol I recognized to be a fellow countryman named Meyer. He was with the Bremen Field Battalion, was severely wounded on the next day and became a prisoner of the French. I asked him about my brother but he had no information. I shared my wine with him, and marched with the patrol back to the farm. Once again I went down into the cellar and returned with mine and Corporal Meyer’s canteen well filled. The men of the patrol emptied my canteen, and Meyer went off with his. Later on, I returned several times to the cellar and brought wine to my comrades in the orchard. At midnight I was posted as a sentry at the tip of the orchard which faced the enemy; I then sat down on my knapsack and fell asleep. As morning dawned, my back-

up-man whose name was Harz and who was also born at the Harz, awakened me and said: ‘Get up and give me some wine! Today will be a hot day, and I will be killed, because I just had a dream that I was hit by a shot in my body; it did not hurt at all, and I fell peacefully asleep again.’ ‘Dreams don’t mean anything,’ was my reply, and ‘Come on now, they are working on a barricade. We will help, to make us warm up; there is no wine left’. We pushed the remaining half of a wagon onto the roadway where the orchard adjoined the buildings; others brought ladders and farming tools; three spiked French cannon were also moved there.

The roaring of French artillery fire reached us as late as midday. We stood behind the hedge ready to fire and looked out for the enemy. Before long, a swarm of enemy skirmishers came up. The crash of a thousand [French] rifles filled our ears, and a jubilant ‘En avant!’ could be heard. They were backed up by two columns of enemy troops of the line that marched at so rapid a pace that we said to each other: ‘The French are in such a hurry because they want to have their meals in Brussels today.’ Only until the enemy came close to our hedge did we open fire; it was so murderous that the ground was covered at once with a mass of wounded and dead.

The French halted for a moment; they then opened a fire that did us great harm. My friend Harz fell down by my side from a ball through his body. Captain Schaumann of the 2nd [Light] Battalion was also killed; my brother had carried him on his back to the farm where he laid him down, but by then he was already dead.

We still did not give up our position. But as soon as the column on the right advanced to the gate of the barn and threatened to cut off our retreat to its entrance, we slowly fell back, firing all the time. Meanwhile our Major Bosewiel had also been wounded. I saw him lying on the ground; he raised himself one more time, but then fell on his face and expired.

The enemy stood already at the entrance of the barn. But we drove him back and were able to enter, although at heavy loss. We then loosed off such a violent fire down the barn towards the open entrance, where the French stood in a dense crowd that they did not dare to enter. I had been at this spot for about half an hour. Then I went to a loophole next to the locked gate that faced the highway. Here, the French were so tightly packed that I often saw three to four enemies felled by a single bullet.

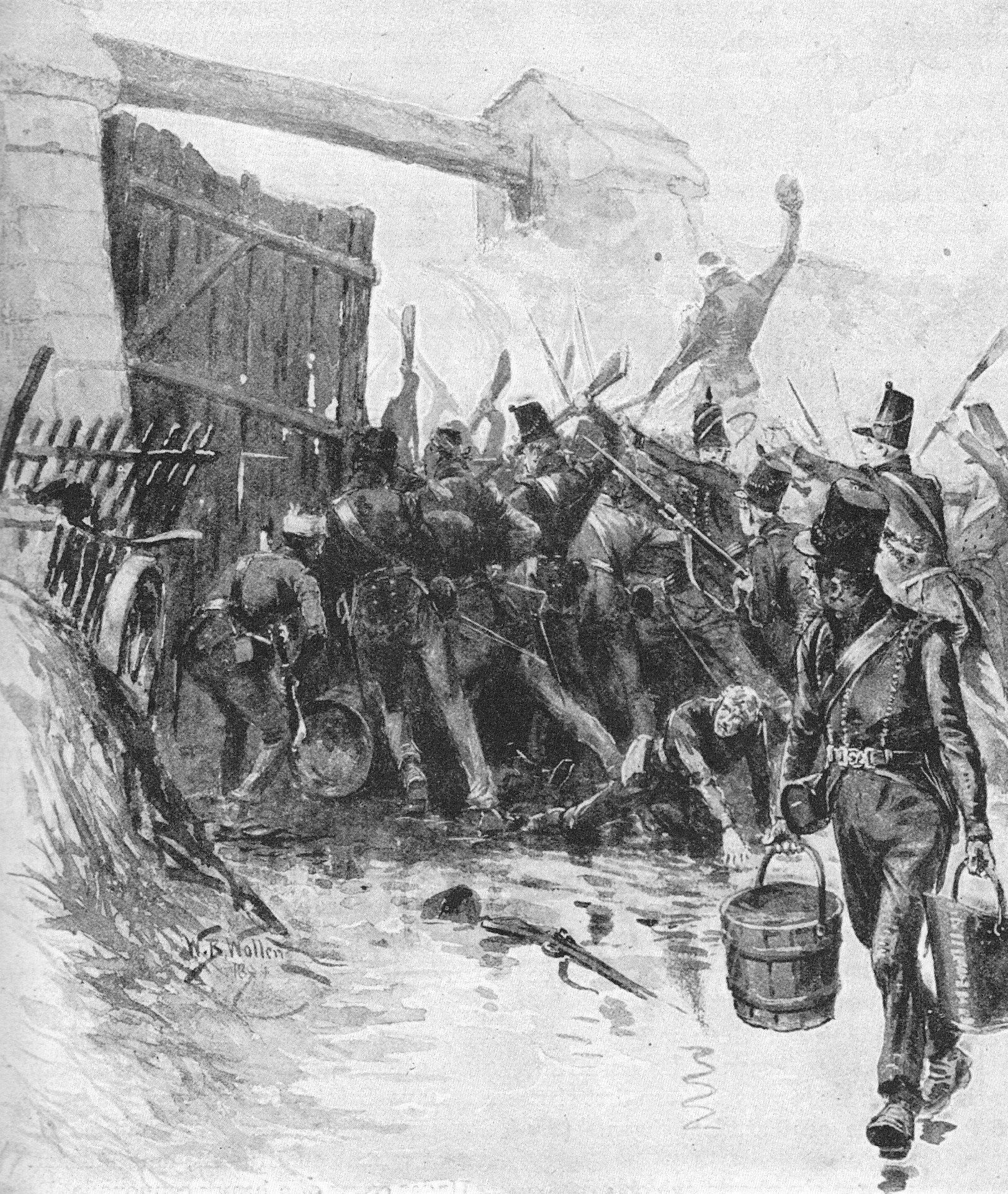

A short time later, our Captain Graeme had the gate opened, and we stormed with levelled bayonets against the tightly packed enemy. He did not resist because we pushed ahead with irresistible fury. I stabbed and hit into that mass like a blind man in a rage. We pursued the enemy beyond the barricade, when English hussars suddenly appeared close to us. They cut so mercilessly into the enemy that a large crowd returned without arms to us and asked for pardon. Upon the hussars’ return from the pursuit, they led the prisoners away.

Posted behind the barricade, we stood by now for a renewed attack, which was hardly half an hour in coming. We easily fought back the skirmishers. But as new columns drove in on us, we retired into the doorway, which I locked up on Captain Graeme’s order. I and several others took position at the loopholes next to the doorway, from where we fired at the enemy wherever he was most tightly packed. We quickly stepped back to reload and let the others take our place. But the French also stuck their muskets in the openings and felled several comrades next to me. Quite a few of ours fell off the scaffolds above us from where they had fired over the wall. But this only enraged us all the more, and I could hardly wait to loose off another shot, and I eagerly reloaded my rifle, so that I must have fired off several hundred cartridges that day.

Ever more [French] regiments were brought up, but they were repulsed each time. One particular enemy officer caught my eye, who rode back and forth on the field in front of us and was giving directions to the advancing columns. I already had my sight on him for quite a while; finally, as he was just bringing on fresh troops, I had him lined up and fired. His horse made a leap, reared up, and crashed down with its rider.

A short time later we made a sortie. I opened the gate; the nearest enemies were bayoneted, the others took to flight. We followed them for a distance and then halted. I now noticed not far away from me the officer that I had shot at. I hurried towards him and grabbed his golden watch chain. But I hardly had it in my hand when he reached for his sabre, shouting abuse at me. I then hit his head with the butt of the rifle that made him fall back and stretch out, and I then noticed a golden ring on his finger. But I first cut a small portmanteau off his horse, and was about to pull off the officer’s ring when my comrades shouted: ’Better get going; the cavalry is upon us!’ I saw some thirty horsemen charge towards us, and with my booty I ran as fast as I could to join my comrades who, with a volley, forced the enemy to retire.

We then stayed for a while on the highway, and the pile of dead enemies made me feel good; they were already lying several feet high, next to the barricade. I saw a grenadier next to the wall who had been shot in the body. He tried to pierce his chest with his sabre but was too weak to do so. I grabbed the sabre by the hand guard in my attempt to throw it away. The Frenchman immediately let go, apparently afraid I might hurt his hands on pulling it off.

Next to the barricade, a wounded soldier was lying in a puddle of water who had been shot in the leg. His pain made him cry out loud as he was trying to roll out of the water. I grabbed him by the arms, another man got hold of his legs, and so we laid him next to the wall, with his head bedded on a dead comrade.

Some 20 to 30 English horses were running around nearby; most were wounded. I called one which stayed put and then let me lead it into the courtyard where I brought it to Major Baring. He, however, ordered me to chase it out of the farm. I then showed him a pouch with gold coins that I had found in my recent booty, the portmanteau, and asked him if I could leave it in his safekeeping. He refused to take it with the words: ‘Who knows what will yet happen to us today; you have to see yourself how best to safeguard the money.’

A short time later, there was another attack on the farm, and my captain ordered me to stay at the gate. But at this time the fighting lasted longer, with ever new columns moving up; we soon ran out of cartridges. As soon as one of ours fell, we immediately emptied the contents of his pouch. Major Baring, who was riding about the courtyard, consoled us with the news that we would soon receive more ammunition.

At that moment I was shot through the back of my head, which I reported to my captain who stood above me on the scaffold. He ordered me to go to the rear. ‘No’, was my answer, ‘as long as I can stand upright I will stay at my post.’ I then took off my neckerchief, wetted it with rum and asked a comrade to pour rum on the wound and wrap the cloth around my head. I tied my shako to the knapsack and reloaded my rifle.

My captain above me, whom I could see whenever I reloaded, often bent himself over the wall, commanding and cursing and hitting into the French. I cautioned him not to bend too far over the wall or else he might get shot. ‘That does not matter’, was his answer, ‘just let those dogs shoot!’ Shortly thereafter I noticed that his hand was bleeding and that he wrapped it with a handkerchief. I then shouted: ‘Captain, Sir, now it is your turn to go to the rear!’

‘Ah, nonsense’, he replied, ‘there is no going to the rear; it is nothing!’ He took his sword with his left hand and kept cutting at the flood of enemies that were rushing up.

Soon thereafter I heard some shouting coming from the barn door: ‘The enemy’s trying to break in!’ I went there, and hardly had I fired a few shots down the barn when I noticed heavy smoke appear from under the beams. In no time at all did Major Baring, Sergeant Reese, from Tundern, and Poppe come running to extinguish the fire with field kettles full of water they had filled at the pond.

As the loopholes behind us were not fully manned, the French vigorously fired at us through these. I and some comrades posted ourselves at the loopholes whereupon the enemies’ fire became weaker. Just as I had fired a shot, a Frenchman grabbed my rifle to tear it away from me. I said to my neighbour: ‘Look here, that dog is pulling at my rifle.’ ‘Wait,’ he said, ‘I have a shot loaded,’ and the Frenchman fell right away. At the same moment another grabbed at my rifle, but my neighbour to the right stabbed him in his face.

Now as I was about to retract my rifle to reload it, a mass of balls came flying by me. They rattled at the stones of the wall; one of them ripped off one of my woollen shoulder rolls, another smashed the cock of my rifle. To obtain another one, I went to the pond, where Sergeant Reese was about to expire; he could not talk anymore. But when I tried to take his rifle; I knew it was a good one, he made a grim face at me. I took another one, there were many lying about, and returned to my loophole. But soon I had fired off all of my cartridges, and before I could keep up firing I searched the pouches of my fallen comrades, most of which were already empty.

So our firing became weaker, and the pressure of the French more forceful. Fire broke out again in our barn, and it was extinguished again. I then searched the cartridge pouches of the dead in the courtyard. Major Baring rode up to me and said: ‘You must go back!’ To him I replied the same that I had already told Captain Graeme; ‘He is a scoundrel who deserts you, as long as there still is a head on one’s shoulder!’

Soon afterwards I heard a general shouting throughout the farm: ‘Defend yourselves! Defend yourselves! They are coming in everywhere; let us draw together!’ Our men had left the scaffold. I observed several Frenchmen on top of the wall. One of them jumped down off the scaffold; but at the same moment I drove my sword bayonet into his chest. He fell down on me and I flung him to the side; but my sword bayonet had been bent and I had to throw it away.

I saw my captain in a hand to hand fight with the French at the entrance of the house. One of them was about to shoot at Ensign Frank, but Captain Graeme pierced him with his sword; another one he struck in his face. I tried to run there to help, but all of a sudden I was surrounded by the French. I now made good use of the butt of my rifle. I thrashed around me until only the barrel of my rifle was left, and freed myself.

Behind me I heard curses and abusive language: ‘Couyons Hanovriens’ and ‘Anglais’, [Hanoverian and English scoundrels] and noticed how two Frenchmen brought Captain Holtzermann into the barn. I was going to free him when suddenly a Frenchman gripped me by my chest from the side. I seized him, too; but then another one stabbed at me with a bayonet. I threw the Frenchman sideways whom I was holding so that he became the one to be stabbed; he let go of me and, shouting: ‘Mon Dieu, mon Dieu!’, fell to the ground.

Now I hurried to the barn through which I hoped to escape. When I found its entrance blocked by a crowd, I leapt over a small partition to where some of my comrades and Captain Holtzermann were standing. Soon a great many Frenchmen moved in on us and shouted: ‘En avant, couyons!’ [Get going, scoundrels!].We were driven out of the corner where we stood and forced to jump over the partition. One of ours who was unable to jump because of his wound was stabbed in his lower body. We were outraged. We cursed the French and were going to go for them; but Captain Holtzermann managed to calm us, even though inside we were seething with rage about such disgraceful treatment that no captured Frenchman had ever received from us.