The Imperial Guards were now clearly recoiling from the murderous allied fire and were returning from the ridge in disarray; and at the very same moment, the awful truth regarding the incessant cannonading on their right had finally dawned upon the French soldiers and the terrible news spread through the ranks like wild fire, it was the Prussians! In one brief moment everything became clear to them, they had been tricked into fighting and lured into a deathly trap. Suddenly their earlier suspicions of their senior officers appeared only too well founded and there were cries of ‘treachery’. Initially individuals, then larger groups started to fall away from the formations as the cry began to spread ‘Sauvé qui Peut’ [Every man for himself].

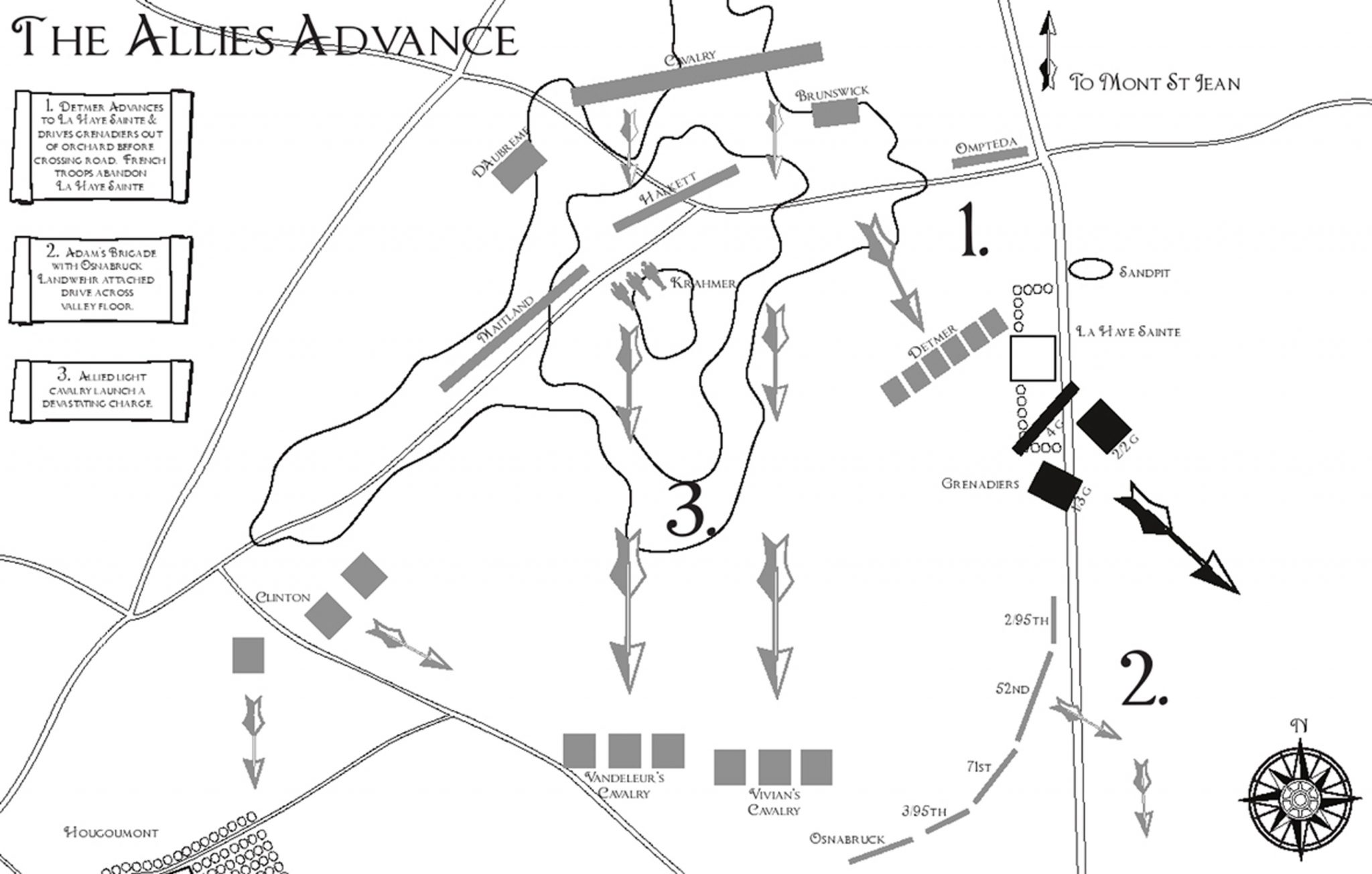

The Duke of Wellington had as usual appeared at the very moment of crisis, and was now in the rear of Colborne’s 52nd. His expert eye had spotted the tell tale signs of a breakdown of morale in the French ranks and with the sound of Blucher’s attack ringing in his ears, he knew instinctively that this was his moment to act decisively. He ordered Colborne to continue his advance and the 52nd marched in line diagonally along the valley floor towards a point just south of the orchard of La Haye Sainte and the remainder of Adam’s Brigade and the Osnabruck Landwehr were ordered to move with them, providing flank guards. Such a march almost perpendicular to the French line would in normal circumstances have proven suicidal, but the Duke was confident in his assessment of the collapse of French morale; he had seen it too often in Spain and Southern France not to recognise it.

Even when Colborne’s men were stopped by troopers of the 23rd Light Dragoons, who had made an incautious advance on the French and now rode across their front as they retired in haste; Wellington was there to urge on their renewed advance with a ‘Never mind! Go on! Go on!’ As Adam’s Brigade marched towards the Brussels – Charleroi highway, they did not meet any organised defence, they simply swept the remnants of the Guards and Reille’s troops out of the valley at bayonet point.

During this sweeping march, the Osnabruck battalion, which hung on the right rear of the 52nd and 71st, came up on a crowd of Imperial Guardsmen retiring at a steady pace in a compact group and they could see a small group of officers valiantly attempting to rally their troops, to continue to offer resistance to the allied attack. Colonel Hugh Halkett had accompanied the Osnabruck Landwehr and as he watched these retreating Guardsmen carefully, he spotted a senior officer, whom he judged to be the commander of the formation, on horseback attempting to halt them, but as they ignored him and continued to retire at pace his horse fell to a shell fragment, which also wounded the officer in the head and he was left behind. Halkett spotted his vulnerability and in a moment of great valour, or extreme stupidity, he urged his horse forward:

‘…I made a dash for the general. When about cutting him down he called out he would surrender, upon which he preceded me [to the rear], but I had not gone many paces when my horse got a shot through his body and fell to the ground. In a few seconds I got him on his legs again, and found my friend, Cambronne, had taken French leave in the direction from where he came. I instantly overtook him, laid hold of him by the aiguillette, and brought him in safety and gave him in charge to a sergeant of the Osnabruckers to deliver to the Duke…’

General Cambronne had been captured, his head bleeding profusely from a deep cut caused by a shell fragment, presumably concussed and disorientated, and he gave himself up with only a minor struggle.

As Adam’s troops advanced across the valley, the simultaneously victorious troops of Detmer’s Brigade were descending from the ridge in pursuit of the Grenadiers of the Guard. Some of these Guardsmen who retired into the orchard of La Haye Sainte, were protected somewhat by the French garrison in the farm complex and they attempted to reform to make a determined effort to hold their position. Chasse urged his troops on and after a short fire fight the Imperial Guardsmenwere forced to retire across the road and to continue to retreat, taking the garrison of the farm with them. Detmer chose to reorganise his troops in the fields to the west of the farm before continuing to advance, presumably only too well aware of his exposed position. However, he was soon reassured by the sight of Adam’s Brigade marching across his front as they arrived near the chaussee to the south of La Haye Sainte.

At this point, the infantry of Adam’s and Detmer’s Brigades had merely swept the floor of the shallow valley. Although the French line was clearly wavering, it was evident that it would need a greater effort than this to smash through it completely.

Recognising the perfect opportunity, Vivian ordered his light cavalry forward, he was supported by Vandeleur’s, Grant’s and Dornberg’s brigades on his right, and accompanied by Gardiner’s fresh horse artillery troop. Manoeuvring the 10th Hussars through Napier’s guns, which failed to cease firing in all the excitement until peremptorily ordered to stop, the rest of the light cavalry passed through the front line and quickly reformed their formations. This was no time to hesitate and immediately they were formed, the cavalry was ordered to ride directly towards the French lines. As they rode down the slope and across the valley floor they left the blinding smoke behind. Lieutenant Anthony Bacon 10th Hussars recalled:

…all at once we burst from the darkness of a London November fog into a bright sunshine.

They rode across the valley to the rear of Adam’s line of advancing troops, and simply launched themselves into the exhausted remnants of the French cavalry and infantry formations. Slashing to right and left until their arms ached, they scythed down the French who offered only a feeble defence and then turned and ran, the effect of the charge of the light horse was truly devastating.

Gardiner’s and Sinclair’s guns; some French units made a valiant attempt at a defence, but suddenly a partial retreat was transformed into a wholesale rout; the majority of the French army simply turned and fled.

The Duke of Wellington saw that it was now or never and riding onto the crest line, he simply waved his bicorn hat in the air with animation and the whole allied line instinctively marched forward into the valley, the movement was simply copied by units further to the right and left who were unable to view the Duke. Everyone just knew that this was the moment of outright victory!

In a valiant effort to protect the rear of this great fleeing rabble as it funnelled into the chaussee leading to Genappe, the two squares of the 1st Grenadiers of the Guard which had been held in reserve near La Belle Alliance, stood like immovable rocks in a sea of despair as did the 1st Chasseurs a little to the rear at Le Caillou. These squares were flanked and supported by a number of cavalry units that retained their cohesion; whilst other Guard units returning from their failed assaults attempted to rally in their vicinity. The remains of the four battalions of the 3rd and 4th Chasseurs formed to the east of the chaussee near Smohain, who with the 2nd/1st Grenadiers sought to hold back the advance of the Prussians from the Papelotte area. Nearer to La Belle Alliance on the road leading to Plancenoit stood another amalgamated square of the Grenadiers. To the west of the chaussee the remnants of three Guard battalions formed an amalgamated mass which stood near the 1/1st Grenadiers; and finally the 2nd/3rd Grenadiers appears to have retired alone in square formation past Hougoumont wood. Meanwhile the remnants of the Guard units in Plancenoit formed a similar reserve to hold off the Prussian advance from there.

Valiant but foolhardy charges by the overconfident British cavalry aiming to overthrow these squares only led to serious losses and soon the cavalry moved on to find less determined foes, leaving them to the infantry now fast approaching across the valley floor.

Lieutenant Henry Duperier of the 18th Hussars recorded in a letter:

After a long contest as I have said before of perhaps half an hour altogether, but at entire close quarters about ten minutes, Lord Wellington brought some little red coated fellows from where I do not know, I could just see them through the cloud of smoke who charged [Colborne’s advance], we shouted and the whole of the French army gave way that very instant, the very finest I ever beheld. We charged, and of course overtook them, in an instant we fell on the cavalry who resisted but feebly; and in running, tumbled over their own infantry. From that we came on the artillery who was not better treated by the Irish lads in attentions. There was perhaps three 18th Hussars on a regiment of infantry of the French nothing but ‘Vive le Roi,’ but it was too late, besides our men do not understand French, so they cut away.

Colborne’s battalion crossed the main highway and the brigade then marched parallel with the road, capturing an entire artillery battery as it sought to flee the field. The Duke of Wellington and Lord Uxbridge followed close behind the 52nd when Uxbridge was suddenly struck in the leg and was forced to retire. Detmer’s troops also had crossed the chaussee and marched through the remnants of the batteries on the forward ridge, capturing a number of guns and then moved on towards the road to Papelotte.

La Haye Sainte had been abandoned almost without a fight (although it is claimed that Lord Somerset was wounded by one of the last shots from La Haye Sainte) and the remnants of the 27th Foot and the grenadiers of the 40th Foot simply walked in to the farmhouse unopposed. Hougoumont wood was cleared by the Saltzgitter Landwehr and two battalions of the Brunswick corps.

Before the Imperial Guard squares could come under close range musket fire from Adam’s troops, whilst overwhelming numbers of allied troops were fast approaching, including Prussian troops from the Papelotte area, the Guard squares began to march slowly away from the field of battle. These stubborn few boldly forced their way into the still seething river of fugitives, but as they moved on, their formations were slowly and almost imperceptibly eroded and finally it would seem that after a titanic effort the last remnants of order were swept away with the torrent apart from the two squares of the 1st Grenadiers who maintained their position.

As Marshal Ney recalled:

The brave men who will return from this terrible battle will, I hope, do me the justice to say that they saw me on foot with sword in hand during the whole of the evening, and that I only quitted the scene of carnage among the last, and at the moment when retreat could no longer be prevented. At the same time the Prussians continued their offensive movements, and our right sensibly retired, the English advanced in their turn, there remained to us still four squares of the Old Guard to protect the retreat. These brave grenadiers, the choice of the army, forced successively to retire, yielded ground foot by foot till overwhelmed by numbers they were almost entirely annihilated. From that moment a retrograde movement was declared, and the army formed nothing but a confused mass.

Finally, the last vestiges of the Guard, the two battalions of the 1st Grenadiers, marched off the field as compact units under the command of General Petit, and forced their way through the torrent of fugitives, sometimes bayoneting fellow Frenchmen to preserve their formation. Their measured withdrawal probably saved many lives from the swords of the Prussian Hussars as they formed the army’s entire rearguard. The setting sun also set upon the invincibility of the Imperial Guard.

The Duke had somehow borne a charmed life that day, always in the thick of the fighting and escaping without the merest scratch, but now his job was done. Indeed Felton Hervey pointed out that there were still dangers as the French retreated; to which he replied:

Never mind Hervey, I believe my life was of some consequence this morning, but it is no matter now.

As the infantry pushed beyond La Belle Alliance the last remains of dusk merged almost imperceptibly into the inky blackness of night. To their left, units of the Prussian army loomed out of the darkness and rapidly passed on in pursuit of the French army. Wellington’s army now halted, often without orders, to allow the Prussians to pass; and having stopped, they all too soon came to feel their utter exhaustion, which even overcame their dreadful hunger pangs and parched throats. Men dropped to their knees or simply lay down where they had stood and only took a passing interest in the procession of Prussian units that filed past cheering their allies, their bands playing the British National Anthem. Most were too worn out to take much notice of the meeting between the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshal Blucher just beyond the inn of ‘La Belle Alliance’, a portentous encounter. Shaking hands Blücher reputedly greeted Wellington with ‘Mein lieber Kamerad!’ and then ‘Quelle affaire!’ which, according to Wellington, was about the only French the old Hussar knew.

The two commanders agreed that the fresher Prussian troops would pursue Napoleon’s forces relentlessly throughout the night, whilst Wellington’s exhausted men could regain their strength with rest.

The French torrent streamed along the chaussee all night and every attempt to halt and reform them was just as rapidly dispersed again by the sounds of Prussian bugles and drums. Napoleon was caught up in the chaos and initially found refuge at La Caillou with his Guard; but later he was reportedly seen incognito, fleeing with only a handful of officers and if recognised, he would rapidly move on. At the bottle neck of the narrow bridge at Genappe, there was panic as the Prussian cavalry approached and a log jam occurred, which the fugitives passed by clambering over on foot; cannon and all manner of vehicles were abandoned on mass, including Napoleon’s coach which was caught in the jam and ransacked by Major von Keller and his men of the 15th Prussian Fusiliers, who claimed that the Emperor apparently only narrowly escaped with his life.

Lieutenant Golz of the Brandenburg Uhlans recounts that General Lobau, commander of VI Corps and Doctor Larrey, head of the French Medical Service were captured at Genappe, the latter initially being badly manhandled by the troops who had mistakenly identified him as the Emperor Napoleon; General Duhesme was apparently killed at Genappe by a Prussian soldier although he may have simply died of his wounds. The treasury and headquarters wagons containing a huge sum in gold coins were caught at the village of Villers and Paymaster Peyrusse issued a number of bags to each soldier of the escort containing 20,000 francs each to pass the river independently; unfortunately for him, cries that the Prussians had arrived caused the mob to overwhelm them and most of the gold was never seen again. Many Prussian soldiers were made rich for life that night, one soldier alone reputedly sending home 5,000 Napoleon’s.

By morning some of the advanced elements of the Prussian cavalry had reached as far as Quatre Bras and Frasnes, giving the French army no opportunity to halt and reform.

Later that fateful evening, Lieutenant Basil Jackson of the Royal Staff Corps rode behind the Duke of Wellington as he slowly led his horse through the wreckage of the battlefield to his quarters at Waterloo village. The Duke rode in silence in serious contemplation of the devastation he perhaps felt at least partly responsible for. He was only too aware of the masses of casualties and the untold pain and suffering being endured by tens of thousands. As he arrived at his headquarters and wearily slid from the back of ‘Copenhagen’, he gently patted his faithful horse on the rump, only to narrowly miss the violent kick he thrust out in retaliation; only the last of many miraculous escapes the Duke had enjoyed that day!

Rest was not however to come easy to his mind that night and in the early hours he wept openly as the list of prominent officers killed and wounded was read to him; many of whom were close personal friends of his. As Wellington himself later said:

‘I have never [before] fought such a battle and I trust I shall never fight such another’