Having pursued the French from the field, the Prussians pushed on all night with their cavalry beating drums and blowing horns to disconcert any attempt to rally the French troops. All attempts at forming a rearguard failed with the first cry of ‘Prussians’ and soon the scattered remnants of a once magnificent army flooded back over the border. By midnight, Blucher had installed himself at the inn at Genappe and began to write his report to King Frederick William.

Blucher then wrote orders for his corps commanders; the I and IV Corps would march to the vicinity of Charleroi. The III Corps still faced Grouchy at Wavre, the outcome of which was still unknown, but the II Corps was to attempt to cut Grouchy’s retreat into France and the exhausted men, having fought all afternoon for Plancenoit, now marched overnight towards Mellery which they reached at 11 a.m.; only to find that Grouchy had gone.

Wellington had returned to Brussels to complete his Waterloo despatch where he met the politician Thomas Creevey, and admitted a number of times that it had been ‘so nice a thing – so nearly run a thing’ and without any sign of arrogance stated honestly his view that

‘By God! I don’t think it would have done if I had not been there!’

His army spent the morning repairing their equipment and searching out the wounded to be transported to the hospitals in Brussels, but that afternoon they then marched to Nivelles at the commencement of their march to Paris.

The French had outrun the Prussian pursuit which had lost contact with the rump of the French army and it was now beginning to rally; although many others had simply returned to their homes. About twelve thousand men of the 1st and 2nd Corps had now collected near Avesnes and these were soon augmented by the remnants of the Guard, the 6th Corps and the reserve cavalry. Meanwhile Soult had arrived at Phillipeville in France where he managed to gather about five thousand fugitives from the army.

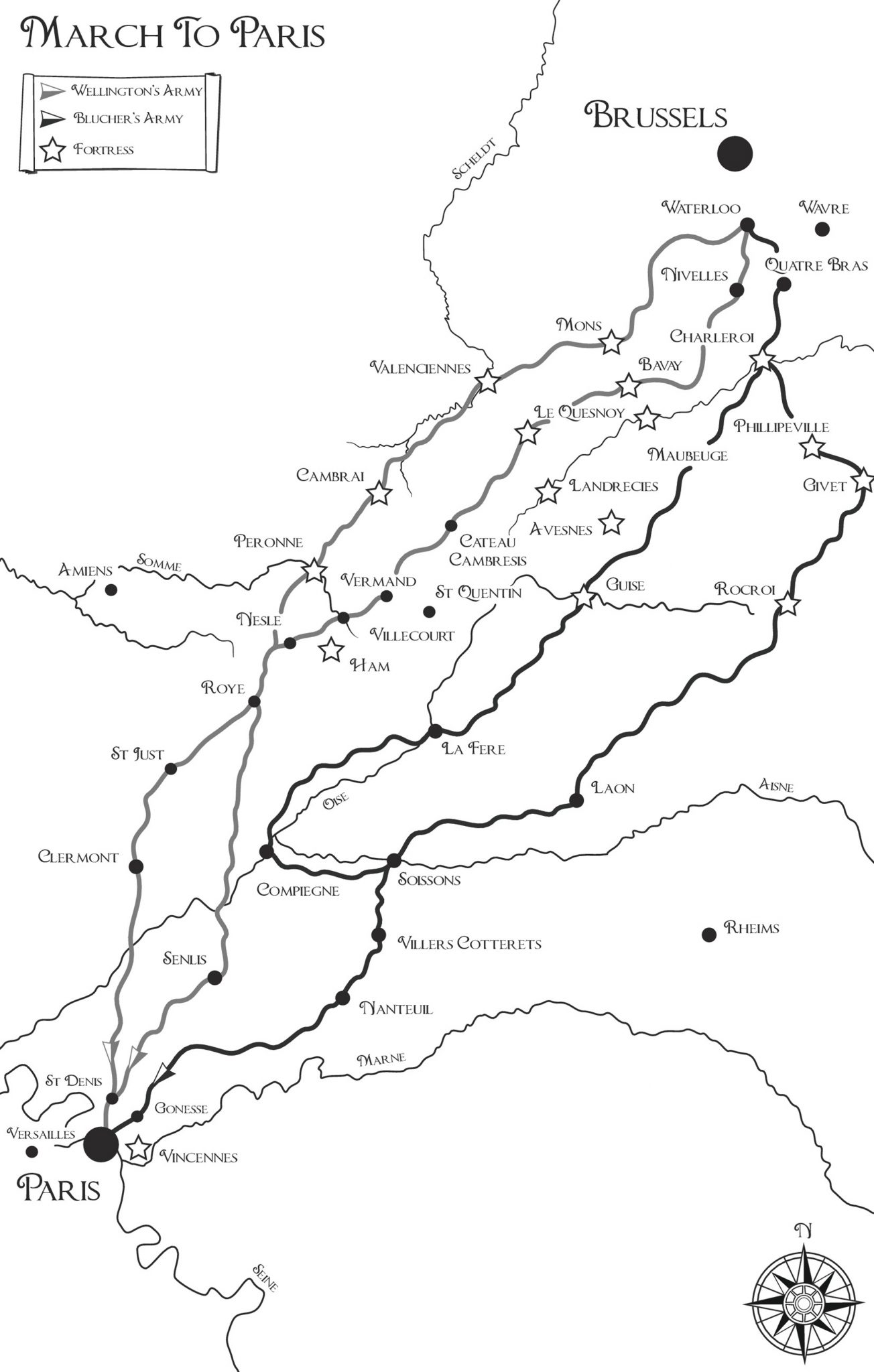

Blucher had already turned his thoughts to Paris and he arranged with Wellington that the Prussian army would march towards the capital on the east of the Sambre, whilst Wellington’s troops marched on the west side of the river. He also arranged for the British to provide huge amounts of musket ammunition and cannon balls to resupply his army and the Duke would also supply siege guns and a pontoon train for bridging rivers. The two generals would supply units from their respective armies to cover and in some cases invest the French border fortresses as they passed. But Blucher secretly planned to arrive at the French capital before his ally so as to gain the glory of entering Paris for Prussia alone. Blucher ordered the army to march to Beaumont and Maubeuge the next day, but still had no news of the III Corps or Grouchy at Wavre since the battle of Waterloo. The Prussian supply chain had broken down under the strains of the last few days, but this did not deter the field marshal, who rather than resting his troops, ordered continued forced marches and allowed his men to provide for themselves by simply taking what they needed from the French towns and villages they passed. This plundering, added to the deep seated Prussian hatred of the French for the humiliations their country had endured over the last decade and produced unbridled savagery, where looting for food was accompanied by wanton destruction, rape, pillage and even murder in some cases. News that the Prussians were arriving led to French inhabitants fleeing for their lives, returning only when they had passed to find the complete and systematic destruction of absolutely everything.

Wellington, with his allied force, took a very different approach. He announced to his troops in a General Order of 20 June that they were entering France as liberators of the French people from the tyranny of Napoleon and as the allies of King Louis XVIII. As such, no person or property was to be harmed nor any supplies taken without payment. He ordered his troops towards Mons and when his slow progress was questioned by Muffling, Wellington explained that by moving more slowly, his supplies could be maintained and his army kept in check. Wellington simply refused to join a race for Paris with Blucher.

As the Duke caught up with his army on the march that day, he stunned the 3rd Division by instantly ordering Count Kielmansegge to place himself under arrest. He was relieved of his command. His performance at Waterloo had unfortunately been misreported by General Alten. Although Wellington, after hearing from a deputation of British Staff officers, soon reprieved Kielmansegge, he did not reinstate him in command of the 1st Hanoverian Brigade.

Napoleon had now found his way to Phillipeville where he hoped to hear of Grouchy; whilst he sent orders to every other unit he could muster to make rapid marches on Paris, but these orders do not seem to have ever arrived, or were simply ignored. Laon was designated the rallying point for the infantry corps, the reserve cavalry were to march towards Rheims and the Guard to Soissons. Napoleon also wrote to his brother Joseph at Paris, informing him of the defeat and revealing his fear that Grouchy’s entire force had been forced to surrender before he rode on to Laon, in the hope of finding his army there.

It is almost always assumed by historians that the march on Paris was virtually unchallenged by the French army and that there were few if any casualties, with the outcome inevitable. This ignores the regular small actions fought with the Prussians in an attempt to stem the allied advance, even though the British advance in their wake was largely uneventful.

On the 20 June there was a sharp rearguard action between Pirch’s Corps and Grouchy’s troops, but the French managed to pass through Namur and escape the Prussian pursuit by setting fire to the only bridge for miles around over the strongly flowing River Meuse. Grouchy had escaped the clutches of the Prussians and could safely retreat into France with a sizeable force which would be invaluable to his Emperor.

By the 21st Blucher had surrounded Maubeuge and Ziethen’s I Corps had arrived at the fortress of Avesnes, which the Prussian artillery immediately commenced bombarding but with little chance of a quick resolution. However, during the early hours a Prussian shell fortuitously landed in the magazine of the fortress, causing a tremendous explosion and the garrison immediately capitulated, thereby supplying huge amounts of heavy cannon and ammunition to the Prussians and also providing a secure base for their supply lines.

The same day Wellington’s forces advanced to Bavay, leaving forces blockading Valenciennes and the fort of Le Quesnoy.

On the 22nd the Prussians blockaded Landrecies and III Corps moved to blockade Givet and Phillipeville; here II Corps was allocated to Prince August of Prussia who would continue besieging the frontier fortresses, whilst the main army proceeded towards Paris. Wellington advanced to Cateau Cambresis and Gommegnies, whilst Prince Frederick of Orange’s Corps took over the investment of Valenciennes and le Quesnoy.

The following day the Prussian forces moved towards Laon where it was reported that the remnants of the French army were reforming, whilst also sending parties to reconnoitre Guise and St Quentin. Meanwhile Wellington ordered his troops to rest this day, except for a detachment under Colville which sought to induce the small garrison of Cambrai to surrender.

By the 24th reports were arriving that the remnants of Grouchy’s Corps, some 40,000 strong, were marching from Reims to Chateau-Thierry as the Prussians approached Laon. Guise capitulated to the Prussians after a short bombardment and Cambrai was stormed by the British, with the French garrison putting up minimal resistance. But

the news that shocked everyone that day was delivered from Paris, Napoleon had abdicated! The emissaries of the French Chamber had reminded Wellington and Blucher that war had been declared on Napoleon, therefore they demanded that the allies now called an immediate cease fire and halt to their march on Paris, Blucher ignored them, whilst Wellington encouraged them to open negotiations with Louis. Both generals however were determined to keep the pressure up by continuing their march on Paris.

It was now suspected that the French would contest the crossing of the River Oise and Blucher sent detachments to all the river crossings in an attempt to seize one or more intact. Wellington however, was not interested in chasing Blucher, his advance cavalry had now reached St. Quentin but his infantry were still near Cambrai.

On the 26th, Blucher ordered an attempt to take La Fère fortress which controlled the crossing of the rivers Oise and Serre, but failed from inadequate artillery. However the fort at Ham did capitulate.

Marshal Davout, on behalf of the Chambers, had ordered Soult’s and Grouchy’s forces to unite at Soissons and when Soult resigned in preparation for his returning to the king’s side, Grouchy was given supreme command of the army of around 29,000 infantry and cavalry but with little artillery. Since the news of Napoleon’s abdication, desertion had also increased markedly.

Having allowed his troops two days rest, Wellington now became more active and his troops set off for Vermand and its surroundings, whilst a detachment sent to Peronne quickly forced the fortress to capitulate.

On the 27th Blucher ordered his army to make a forced march to Compiegne, where they captured the bridge over the Oise intact. d’Erlon made a number of half hearted attempts to regain Compiegne whilst every available French unit marched as fast as they could through Villers-Cotterets to Senlis and on to Paris, to prevent the Prussians arriving at their capital city before them.

That evening, the Prussians caught one French column completely by surprise, near Viller-Cotterets, capturing 14 cannon and numerous prisoners. The following morning they drove into the town, scattering the defenders who fled in disorder, some back towards Soissons and only a few towards Paris. Further attempts were made by the Prussians to prevent the French forces at Soissons reaching Paris, but they were eventually brushed aside by Vandamme’s troops and the French marched on to Nanteuil-le-Haudouin. Continual skirmishes dogged the French cavalry rearguard with further Prussian and French cavalry clashes at Senlis.

Meanwhile Wellington had accelerated his advance, crossing the Somme on the 27th at Villecourt and proceeding through Nesle and Roye towards St Just-en-Chaussee.

By the 29th all the scattered remnants of the French army had crawled into Paris, but it was clearly in no position to put up a serious defence against the allies.

Blucher’s forces now faced Paris, the ultimate prize, with Wellington a couple of day’s march behind, but Blucher was unsure what he faced. As early as 1st May Napoleon had ordered Davout to prepare the defences of Paris; three hundred ship’s cannon had been ordered to Paris and five thousand labourers organised to prepare a line of defences along the heights of Montmartre, including a number of strong redoubts. The crossings over the Ourcq canal were defended by earthworks and to the east the fortress of Vincennes was fully prepared to defend itself. The preparations for the defence of Paris on the north bank of the Seine were strong, but those to the south had yet to really begin. To the west a number of bridges had been destroyed but some still remained intact, making them a valuable prize.

Paris could boast about eighty thousand defenders, mostly National Guards and six hundred cannon, but morale was very low and few were keen to continue the fight. The Chambers declared that Paris was in a state of siege and that every able bodied male was required to aid the construction of the defences.

Blucher moved his army up to St Denis and Gonesse on 29 June and reconnoitred the heights of Montmartre. He immediately ordered the IV Corps to attempt to cross the Seine at Argenteuil but all available boats had been removed by the French. But early that morning, Blucher received information that Napoleon was at Malmaison with only four hundred men. Major von Colomb was ordered to launch a daring raid on Malmaison with a combined force of cavalry and infantry; they marched through the night but were thwarted by finding the bridge burned down and then received news that Napoleon had already left. However, von Colomb heard that the bridge at St Germain had not yet been broken down and hurrying there, surprised and overwhelmed a small French force whilst in the act of demolishing it and soon captured another bridge at Maisons.

Realising that the Montmartre front could only be taken with a very powerful attack which would inevitably be very costly, Blucher looked to the west to cross the Seine and then to attack the south of Paris which he saw as a major weak point.

Orders from Blucher to assault Aubervilliers on 30 June, to seek a passage over the Ourcq Canal led to the Prussians being repulsed with a bloody nose. However with the news that von Colomb held the bridges at St Germain and Maisons, Blucher ordered his troops to march as quickly as possible to reinforce this position.

Wellington meanwhile had now neared Pont St Maxence and on the 30th the Duke met Blucher at Gonesse to coordinate their response to the continued pleas for a cease fire from the French delegates.

The Prussians moved rapidly to the bridges and crossed before the French realised what was happening. On the 1st July the French counterattacked at Aubervilliers, driving the Prussian forces back until they were heavily reinforced. The Prussians then recovered and held the position until relieved that night by Wellington’s troops which had finally arrived near Paris.

Wellington now held Gonesse and Aubervilliers and Bulow’s troops marched to join Blucher at St Germain. Von Sohr was sent forward again with two regiments of Hussars and actually reached Versailles, where 1200 National Guards declared for the king and opened the gates, he then continued his march to Longjumeau. Hearing of this Prussian advance, Exelmans launched twelve regiments of cavalry with a small number of infantry, some marching towards the Prussian front and some passing around each flank to cut off their retreat. Sohr discovered the French cavalry column and a regular cavalry action occurred at Villacoublay with the Prussians initially gaining the upper hand. But with further French cavalry approaching, the Prussians were forced to make a fighting withdrawal towards Versailles. At this point, the Prussians found every exit from Versailles sealed and with Exelmans troopers soon arriving, they realised that they were trapped and only a lucky few escaped death or capture.

On the 2nd of July Blucher planned a concerted advance on Paris on a broad front from the south west, but the French were expecting them. The Prussian advance was held up by intense musketry as it neared Sevres but they forced their way slowly forward until finally stopped by the French at the river, as they threw off the already loosened planks as they crossed the bridge.

During the night, Prussian pioneers completed two pontoon bridges at Argenteuil and Chatou which secured the communications between Blucher’s and Wellington’s armies.

French attempts to attain a cease fire had so far achieved little but on 28 June Grouchy had made direct proposals for his corps alone, which would have taken his force out of the defence of Paris; but Blucher’s demands were too much for the Frenchman to stomach and the negotiations failed. The French negotiators then requested and were granted permission to go to Wellington on 29th. The commissioners were informed by Wellington that the removal of Napoleon was not enough to secure a cease fire, Napoleon’s son was unacceptable as the replacement as head of state and neither were any of the French princes; effectively the return of Louis XVIII was the only acceptable alternative. However, the French commissioners continued a dialogue with Wellington, whereas Blucher declined to discuss matters further and simply threatened to sack Paris if it did not surrender.

On 2 July Wellington wrote to Blucher explaining his position, believing that an attack on the city would be costly and was doubtful of its success. He proposed that the French army would need to draw off beyond the Loire and that the ‘vain triumph’ of entering Paris should be foregone to allow Louis to enter Paris without an escort of foreign troops. Blucher could not agree to these terms, the return of Louis not being a priority for Prussia whilst the capture of Paris was seen as a major point of honour.

Davout was informed on 2 July that the Provisional Government had decided to seek a cease fire by sending the army out of Paris, but the marshal was not going to leave without even a token resistance. All the available French troops remaining were moved overnight to Montrouge and at 3 a.m. on the 3 July a heavy barrage commenced on the Prussians at Issy followed by a strong infantry attack. The Prussians fought stoutly and eventually drove the French columns back, both sides each losing over a thousand men killed and wounded; these were the last shots of the Waterloo campaign fired in anger.

At 7 a.m. that morning, the French artillery fell silent and the French offered to sign an immediate capitulation. Blucher arranged to meet Wellington at St Cloud and later that day the Convention of Paris was signed.

The French army commenced the march out of Paris on the 5th of July, whilst order was maintained at Paris by Marshal Massena with the National Guard. Wellington had occupied the northern and western suburbs of Paris and on 6 July the Prussians placed troops near each of the 11 gates of Paris south of the Seine and began repairing the bridges.

On 7 July the allies occupied Paris and Muffling was appointed Governor of the city, with two commandants, one for each bank of the Seine, British to the north and Prussian to the south.

The campaign of 1815 or of Waterloo is often referred to as ‘The Hundred days’. This was first mentioned by Count Chabrot, Prefect of the Seine, when he made a speech welcoming the return of Louis XVIII to Paris on 8 July 1815 with the words:

One hundred days have elapsed since the fatal moment when your majesty… quitted your capital amidst the tears and consternation of the public.

Within days the larger part of the allied armies began to move to more comfortable cantonments in the villages surrounding Paris; the Prussians around Fontainbleu and westwards as far as Evreux and Chartres; whilst Wellington’s troops remained closer, in the Bois de Boulogne and the nearby villages.

Despite the peace, Blucher still looked to humiliate the French and sought to blow up the Pont de Jena, named to commemorate the famous victory over Prussia in 1806, but was prevented from accomplishing it by Wellington placing British sentries on it. He then sought to destroy the column in the Place de Vendome, modelled on Trajan’s Column in Rome, which was decorated with brass reliefs made from the brass of captured cannon from the wars to commemorate the Battle of Austerlitz. The Prussian king put a stop to this barbarism on his arrival at Paris.

However, the allies did restore many of the art works of Europe to their rightful owners, the French armies having pilfered them during the wars to enhance the collection at the Louvre in Paris. The Parisians were appalled by this act and crowds of surly Parisians silently voiced their disapproval, leading to armed escorts being employed as the items were removed.

The fighting was finally over at Paris but isolated fortresses held out for many months; whilst diplomacy became the order of the day.

Napoleon surrendered to HMS Bellerophon at Rochefort on 15 July and was transported to St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died on 5 May 1821 of stomach cancer.