The story of the gallant contest for Chateau Goumont, or Hougoumont as it is more commonly known, has often been told; but strangely, some important events in the heroic struggle for this farm complex have been misunderstood, misrepresented or simply ignored by historians, almost ever since the very day of the battle. The battle for Hougoumont was virtually a battle within a battle and therefore its story can be told for the most part as one. However, such was the nature of the isolated fighting, with few certain reference points, that there are immense difficulties in producing an exact timeline for these events.

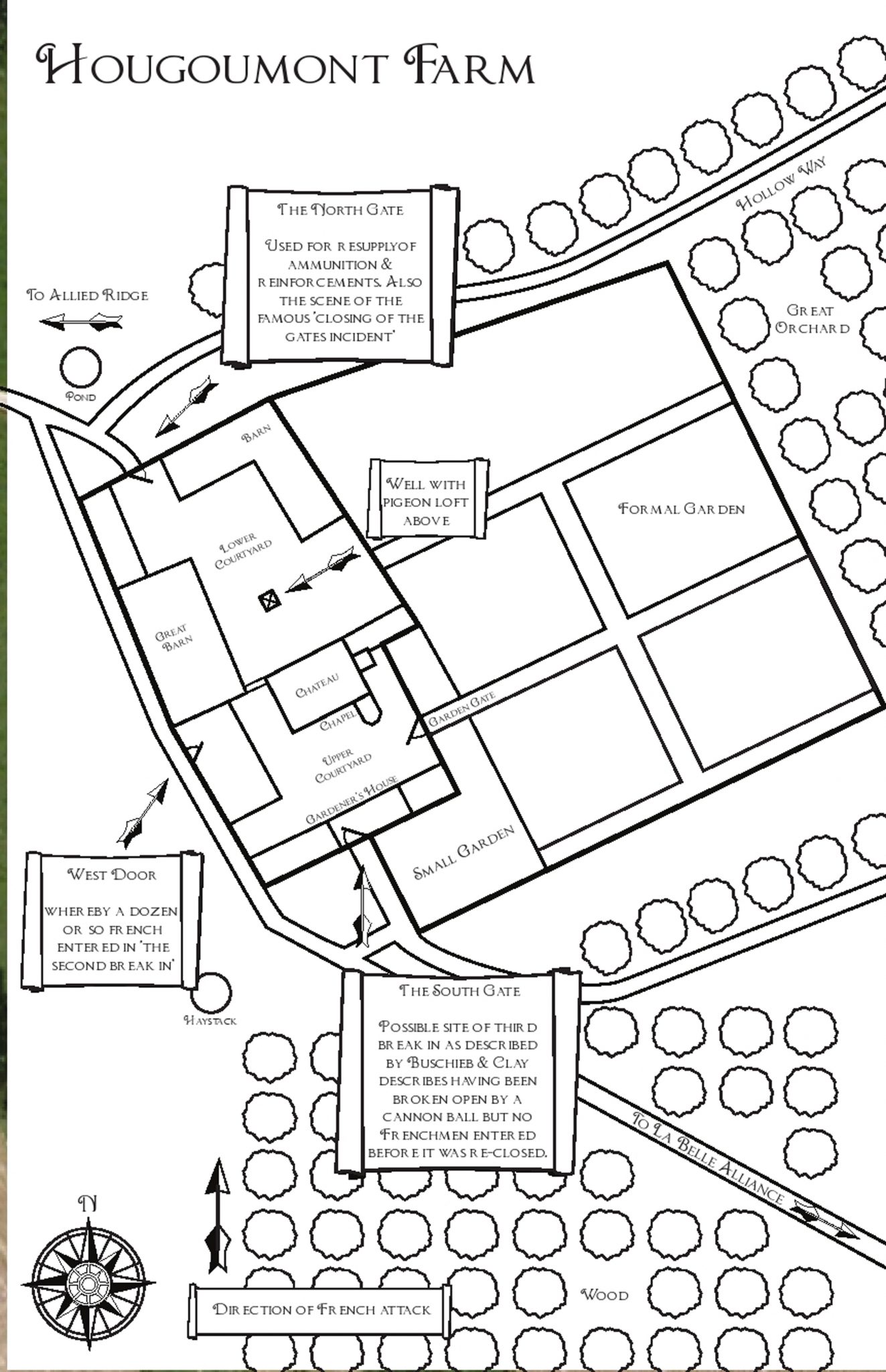

The chateau and its associated staff residencies and numerous agricultural barns and stables, formed a figure of eight shape, surrounding two distinct courtyards. With high stone walls connecting all of the buildings and surrounding the large formal gardens on its southern and eastern boundaries and its northern edge protected by a thick hedge and a sunken track or hollow way, it formed a very strong defensive position. Only four gates allowed ingress to the farm complex, restricting any attacker to assaulting one or more of these points of access. The south (or upper) gate, formed from two great wood panelled doors, secured by a wooden bar, gave access for carriages and carts into the southern (or upper) courtyard through a high archway built underneath the gardener’s house. Another large pair of wood panelled gates secured by a heavy wooden beam was to be found in the high north wall giving similar access for wheeled transport into the much larger northern (or lower) courtyard, which should be viewed as the farmyard. Within this yard was a brick draw-well topped with an ornate pigeon coop. The location of Hougoumont is in low lying ground and then being fronted on its south side by an extensive wood further improved its defensive capabilities. A small arched doorway led from the southern courtyard into the walled formal garden and was thus safe from assault as long as the garden wall was held. Lastly, but very significantly, there was a fourth point of access via a single wooden door in the west wall, which allowed pedestrian access from the lane and adjoining kitchen gardens running down that side of the complex into a barn, from which there was direct access to the southern courtyard. Outside of this walled enclosure, to the east, stood a large orchard bordered by thick, almost impenetrable hedges and to the south, a large wood which completely restricted the view of the chateau complex from that direction making aimed artillery fire impossible from the main French position. The wood ended a full thirty yards from the walls of the formal garden, leaving a corridor of open ground which was to become a veritable killing ground during the battle.

Around 6 p.m. on the evening of 17 June, as the last remnants of the army arrived into Wellington’s chosen position in front of Mont St. Jean after its retreat from Quatre Bras, General Cooke, commanding the 1st Division, consisting of the four Guards battalions, was ordered to send the light companies from each of these battalions to occupy the chateau and its environs and prepare it for defence. On arrival at the complex at about 7 p.m. the four companies of Guards under the overall command of Colonel Macdonell, found a few French infantry and cavalry investigating the complex, most likely with a view to plunder rather than occupancy, and were easily chased off. The farmer had already fled but the Guards did find the gardener, one Guillaume van Cutsem, although his subsequent claims to have remained during much of the battle and survived unscathed appear doubtful.

The two light companies of the 2nd Brigade under Lieutenant Colonel James Macdonell occupied the farm complex and walled garden and the light companies of the 1st Brigade under Lord Saltoun occupied the orchard and wood.

Low firing steps were prepared of stone or wood to allow the defenders to raise themselves over the six foot high wall to fire whilst being able to step down into cover when vulnerable as they reloaded, loopholes were gouged out of the wall which further increased the density of fire and stockpiles of ammunition were arranged in the gardener’s house. The southern gate was barricaded internally with heavy logs and any handy farm implements and other paraphernalia; the north gate was left free to allow access for reinforcements and re-supply, for ease of communication with the troops on the ridge behind and almost certainly as an escape route if things should go wrong.

On the morning of the 18 June, the Prince of Orange decided to reinforce the Hougoumont area before the fighting commenced. Count Kielmansegge supplied the 1st company of the Hanoverian Field Jagers (sharpshooters) of one hundred men and one hundred rifle armed men from each of the Luneburg and Grubenhagen Hanoverian battalions, these three hundred men were all pushed into the orchard. With such a sizeable reinforcement, Saltoun was ordered to return to the ridge with his two light companies. On route, Saltoun met Wellington who was not aware of his withdrawal and ordered him to halt where he was, however hearing nothing further, he eventually continued to rejoin his brigade.

Wellington proceeded to inspect the defences of Hougoumont, ordering the light company of the Coldstream and 3rd Guards to the west of the farm covering the haystack and lane; and ordering the Nassau and Hanoverian troops into the wood. At 9 a.m. the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Nassau Regiment commanded by Major Büsgen, totalling 800 men in six companies, had been ordered from the extreme left wing of the army over to Hougoumont. It took some time to march across the face of the whole army and on arrival just after 10 a.m. Büsgen placed three companies, totalling four hundred men, in the orchard and three companies within the farm complex, which he found empty but prepared for defence, the light companies of the Coldstream and 3rd Guards having previously moved into the western lane area. The Grenadier company of the Nassau battalion occupied the gardener’s house and guarded the south gate, planting their colour defiantly on the rooftop, the other two companies lined the garden wall. Part of the light company of the Coldstream Guards continued to hold the buildings of the lower courtyard and defended the north gate.

And so, as the first cannon bellowed out the commencement of the battle at around half past eleven, Napoleon’s very first action was to order his brother, Lieutenant General Prince Jerome to take the complex with his 6th Infantry Division totalling just over five and a half thousand men. It was apparently intended as a diversion, but this was soon to be no mere feint. Whether on his own decision or following orders from Napoleon is unclear, but the attack was continued with great vigour. Jerome has been much criticised by history as the scapegoat for his decision to press the attacks, but it should be noted that his superior, General Reille, although he later claimed that he ordered him to desist in the attacks, did not stop him, in fact he actually fed the rest of his troops into the later assaults.

This first attack commenced with a cloud of French skirmishers driving into the wood, supported by the formed infantry of Bauduin’s Brigade and flanked by Pire’s cavalry to the west, which slowly forced the Nassau and Hanoverian troops back, until finally pushing them out of the wood into the orchard and then pursuing them through the orchard to the hollow way on its northern boundary. At this point, some of the three Nassau companies appear to have routed and left the field.

The French continued to make an assault on the garden but were mown down by the heavy fire from the wall each time they attempted to cross the thirty yards of the killing ground between the wood and the garden wall. Some survived to reach the relative safety of the wall and desperately tried to wrench the muskets from the defenders as they poked them through the loopholes to fire, often gashing their hands on their bayonets. Others sought the aid of colleagues to raise them up and over the wall, only to receive a musket ball at point blank range or a sharp stab from a bayonet, but none crossed the wall alive. Even their commander Bauduin was killed in the fierce fighting in the wood.

Some brave individuals attempted to force the southern gate, a few of whom may apparently have succeeded; and as the Nassau troops were never in the northern courtyard it may have been at this moment that poor Lieutenant Diederich von Wilder of the Nassau Grenadiers was chased by a Frenchman towards the farmer’s house. As he grasped the door to enter, the Frenchman struck a blow with his axe that severed his hand completely. These few Frenchmen were however quickly shot or bayoneted by Sergeant Buchsieb and his men and the door re-barricaded. Following this close call the battalion’s standard was removed from the rooftop and Buchsieb was ordered to take the colours to safety behind the ridge. At the Hollow Way, the remaining Hanoverian troops were reinforced by Saltoun’s two Guard light companies which had been sent forward again. Together they drove the now disordered French out of the orchard, pushing them back into the wood and then proceeded to set up a defensive line at the hedge line on the edge of the orchard. During their advance the French had also suffered severely from well directed cannon fire from the ridge behind Hougoumont, and particularly after Sir Augustus Frazer had directed Major Bull’s battery of 5½ inch howitzers to throw shrapnel shells into the woods, which the gunners did with great skill causing very heavy losses.

Prince Jerome was not so easily thwarted, however, and he immediately ordered his 2nd Brigade commanded by Soye to join a second assault on Hougoumont. This time Bauduin’s Brigade would attack to the west, supported again by Pire’s cavalry, whilst Soye moved through the wood to renew the attack on the orchard and garden wall.

The light company of the 3rd Guards and part of the Coldstream light infantry totalling around one hundred and fifty men were now outside the farm complex on the western side and were to bear the brunt of this assault, being driven slowly back along the western face of Hougoumont. Arriving near the north gate, the Guards looked to retreat into the northern courtyard, but the leading elements of 1st Legere Regiment were hot on their heels. Sergeant Ralph Fraser armed only with a pike fought with Colonel Cubiѐres, commander of 1st Legere, dragging him from his horse, when the sergeant leapt onto the horse and rode through the north gate; Colonel Cubiѐres was wounded, but survived.

Private Matthew Clay, of the 3rd Guards is an important eye witness to the fight for Hougoumont. He was only twenty years old and new to war when he found himself fighting only feet away from the French outside Hougoumont, whilst the north gates were fought over. The advanced elements of 1st Legere reached the gates finding them apparently closed, but it appears that the cross beam had not been put in place properly; at their head was a giant of a man, Sous Lieutenant Legros, known as L’Enfonceur, or ‘the smasher’. He seized a pioneer’s axe and swinging it against the panels of the gate, forced his way into the farmyard. A large number of French infantry followed him into the courtyard through the narrow gap, forcing the defenders to engage in a desperate hand to hand combat, whilst others retired to the relative safety of the surrounding buildings and commenced firing on the assailants from the windows and doorways. The fall of Hougoumont was resting on a knife edge when Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Macdonell ran forward, gathered a small group of officers and men to him. Together they fought their way to the gate and with the aid of Corporal James Graham, pushed the gate closed, despite the continued efforts of more French infantry to enter. The gates were secured and barricaded, Macdonell eventually securing the gates properly by dropping the great crossbar into place. All of the French infantry who had entered the courtyard were killed, including Legros.

The present threat to the farm eased as the French infantry retired slowly to the south in the face of a determined counter attack ordered by Major General Byng who had sent three companies of the Coldstream Guards , led by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Woodford, down from the ridge and driving the French troops slowly back down the western lane into the wood. The reinforcement then filed into the farm complex via the small west door and greatly boosted the number of defenders within. Woodford was actually senior to Macdonell, but he generously agreed for Macdonell to retain the command and they fought the battle together for the remainder of the day. Now all but two companies of the Coldstream Guards, which remained upon the ridge with the colours, were engaged in the defence of Hougoumont. Most of these much needed reinforcements were positioned along the east wall of the garden where they could support the infantry defending the orchard, but some also relieved part of the Nassau Grenadiers in the defence of the gardener’s house, these then joined their colleagues lining the south wall of the garden. This also allowed the north gate to be reopened for re-supply and to allow the walking wounded to retire, it was also the opportunity for Private Matthew Clay and his colleague, who had been trapped outside, to enter the relative safety of the farm complex, where he was soon put to work defending the chateau itself.

Although there were significant intervals between some of the major attacks, the defenders were given no opportunity to relax, for French skirmishers never ceased firing upon any perceivable movement, making the archway between the southern courtyard and the formal garden particularly dangerous. Although the farm was largely hidden from view from the south by the wood, it was clearly in the view of the artillery attached to Pire’s cavalry to the west on the Nivelles road and was regularly fired upon with solid iron cannon balls in an attempt to breach the walls. A number did smash through the walls or roofs, but luckily for the defenders many of the smaller calibre rounds bounced off the solid masonry, the walls withstanding much of the heavy battering.

A third major attack was launched by Jerome just before one p.m. which was now sent to probe the south east side of the orchard. The obvious danger of this attack, was that the capture of the hollow way would both isolate Hougoumont from the main ridge and allow the French to fire into the formal garden from the rear hedge (there was no wall here) and probably force the defenders to abandon the garden, increasing the isolation and vulnerability of the defenders of the farm complex.

This attack was made by Foy’s Division from Reille’s Corps, led by Gautier’s Brigade and proceeded through and alongside the eastern edge of the orchard, driving Saltoun and the Hanoverians back slowly. In the nick of time two companies of the 3rd Foot Guards commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Francis Home were sent to reinforce Saltoun and together, with the support of fire from the Coldstream Guards lining the eastern wall of the garden, the French were once again expelled from the orchard with heavy losses.

Following such intense fighting, concern was now raised over the dwindling ammunition supplies, as most of that previously stockpiled had now been issued. Ensign Berkeley Drummond, Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion 3rd Foot Guards, informed Captain Horace Seymour, Aide de Camp to Lord Uxbridge, that there was a great need for musket ammunition. Seymour rode back and soon discovered a private of the Wagon Train in charge of an ammunition cart. Without hesitation, despite the heavy musketry fire from French skirmishers in the lane, the private hastily drove his wagon forward and successfully delivered the vital ammunition.

The French then dragged a howitzer forward which began to shell the buildings of Hougoumont from a position in the north east corner of the wood. Saltoun realised that this new threat was very serious and sought to silence it. He attempted to advance into the woods with most of his available force, but soon realised that he was heavily outnumbered and was forced to retire with loss and actually fell back as far as the hollow way. Saltoun’s light infantry companies were now badly depleted and so completely exhausted that they were relieved around 2 p.m. by three more companies of 3rd Foot Guards under Colonel Francis Hepburn who then assumed command of the orchard for the remainder of the day.

Other units were now moved up to fill the position previously held by the 2nd Guards Brigade on the ridge and the 1st Brigade of the King’s German Legion was brought onto the front slope in rear of the orchard to support the troops within.

Just before 3 p.m. another large body of troops was seen advancing from near La Belle Alliance. The division of General Bachelu, moved down the track which still exists, apparently making their way towards Hougoumont but concentrated artillery fire from the allied ridge appears to have caused such heavy casualties that this movement was halted and the assault to be abandoned before the infantry actually became engaged; although an order to desist is also possible.

Around this period, Byng took command of the 2nd Division, Cooke having been wounded, giving Hepburn command of 2nd Guards Brigade and therefore responsibility for the defence of Hougoumont.

The French artillery now changed their tactics and a number of howitzers were employed to fire the farm complex with ‘carcase’ projectiles. Soon the success of this new tactic was self evident as the roofs of the great barn and the chateau were clearly aflame. Many of the wounded had been collected in the great barn and although some were rescued by brave individuals who battled the intense heat and flame (including Corporal James Graham of ‘closing the gate’ fame, who saved his wounded brother here), many more were consumed by the inferno.

Wellington saw the fires and sent advice, written in pencil on a slip of ass skin stating ‘I see that the fire has communicated from the hay stack to the roof of the chateau. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling in of the roof, or floors. After they have fallen in occupy the walls inside of the garden; particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the embers in the inside of the house’.

At this point the defenders would be struggling with the intense heat from the searing flames, choked by thick acrid smoke, beset by the screams of the wounded and neighing of frenzied horses caught in the burning buildings, and stung continually by the incessant crashing of shells and rattle of musketry all around, and yet they fought on.

Private Matthew Clay had been posted in the top room of the chateau and was all too aware of the flames spreading across the main roof below his position. Ensign Gooch stood across the doorway with sword drawn forbidding any one to leave until the position was truly untenable; eventually, fearing that the floor was going to give way at any moment, Gooch released them and in their rapid descent several of the men injured themselves. Clay found his way out of the chateau, no doubt relieved to be safe from the inferno, only to discover himself facing French infantry within the southern courtyard! The west door had been forced and at least a dozen Frenchmen had entered the barn and found their way into the courtyard. Fierce close combat had broken out between the Nassau and French troops and the fortuitous arrival of the Guardsmen[7] from the burning chateau provided a most useful reinforcement. Some of the French infantrymen managed to retire via the same door with seven Nassau prisoners before it was sealed again, however those trapped within the yard were finished off and few captured, Clay claims that only a lone French drummer boy was saved.

The flames were to eventually consume almost every building in the complex except the gardener’s house on the southern face. However, in what appeared to many as miraculous intervention, the small chapel, although attached to the chateau, did not burn and even though the flames licked through the chapel doorway and charred the feet of the huge wooden crucifix affixed just inside above the doorway, the flames never took further hold and the chapel was preserved.

Clay was now posted in the archway of the southern gate which he says was blown open by a cannonball but then closed and secured before any French infantry could react to this opportunity. Later he was moved upstairs into the gardener’s house, which he found in ruins from the intense cannonade from the direction of the Nivelles road.

The allied ridge was now under sustained cavalry attacks; to support this assault and to further prevent the Hougoumont garrison from injuring the flanks of the advancing cavalry with heavy musketry fire, a further assault was also launched upon Hougoumont. Bachelu’s Division, supported by two regiments from Foy’s Division drove into the orchard from the south east and rapidly overpowered the defenders, forcing them back to the hollow way. But here again, under intense fire from the hollow and on their left flank by the Coldstream Guards lining the eastern wall of the garden, the attack stalled and was then forced to retire with very heavy losses and the orchard was recovered.

A little later, another major assault was made by Foy’s Division from the same direction, whilst Jerome made another assault on the farm buildings. Exactly the same sequence of events was played out in the orchard, with the allies initially being forced back to the hollow way and then the French assault being destroyed in the crossfire from the troops in front and those lining the garden wall on their flank, the inevitable outcome was a French withdrawal and the allied troops repossessing the orchard. The attacks upon the farm complex were now noticeably more circumspect and half hearted and the defenders rested uncomfortably, suspecting that at any moment another fierce attack was yet to come.

The allied force defending Hougoumont, probably never exceeded three thousand troops, with another three thousand in close support, but by their stubborn defence, they exhausted the strength of no less than thirteen thousand French troops of Reille’s Corps.