The Duke of Wellington had only offered battle with the assurance that Prince Blucher would send at least one corps to join the battle. Knowing that the Prussians had been at Wavre the previous night and assuming that they would march with first light, around 4 a.m. the Duke had confidently calculated on receiving Prussian aid before the battle actually commenced, or at least no later than 11 a.m. He therefore spent the morning expectantly awaiting news of their arrival, but he was to remain disappointed. Nervous for news, patrols were frequently sent out beyond his left wing seeking reassuring information. This first came around 10 a.m. from a Major Thomas Taylor of the 10th Hussars, who reported having met a few Prussian officers at Chapelle St. Lambert, they had confirmed that a Prussian corps of twenty five thousand men under General Bulow was approaching and were presently about five miles away from them. With the news that the Prussians were coming soon, Wellington could concentrate fully on the battle in his front.

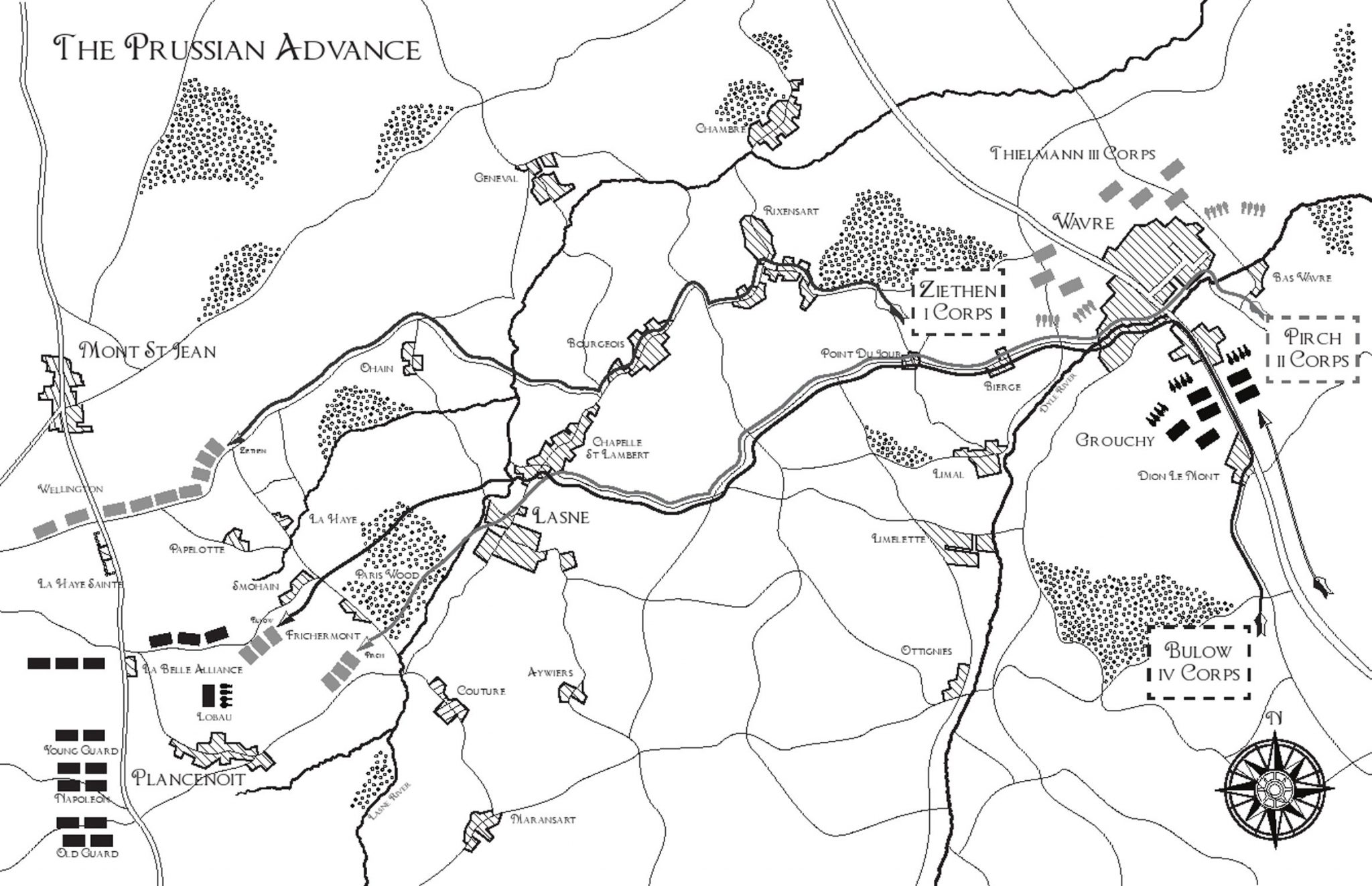

But the arrival of the Prussians was to be delayed greatly beyond Wellington’s expectations because of the poor condition of the roads. Bulow’s corps, being the freshest and largest, had been ordered to march at dawn from their overnight encampment at Dion le Mont, three miles south east of Wavre. This corps was the furthest away from Wellington’s position which complicated issues, as it had to march past the encampments of the other corps and delayed their own march for many hours. The 15th Brigade led the march; they set off as ordered at 4 a.m., however due to subsequent delays the rear of the corps was only just setting off from the camp six hours later. And to make the situation worse, as the rearguard troops began to march off, the baggage train was attacked by Exelman’s cavalry which caused the 1st Silesian Landwehr and 2nd Pomeranian cavalry Regiments to retrace their steps to drive the French away. They successfully drove the French cavalry off but these regiments subsequently failed to arrive in time to fight at Waterloo.

Because of the proximity of Grouchy, it was deemed too dangerous to march westward on the south side of the River Dyle, therefore the entire corps was ordered to pass the narrow bridge and road through Wavre which was a major bottleneck. The situation was not helped when a fire broke out in the town, but it only transmitted to a couple of houses and the troops and artillery of Bulow’s Corps were soon able to continue their march.

Having passed Wavre, the troops continued on the road for Chapelle St. Lambert and the leading elements of Bulow’s corps began arriving there soon after 10 a.m. The II Corps of General Pirch was to follow Bulow, but was also forced to halt by the fire at Wavre and it was gone 4 p.m. before the whole of his corps had passed Wavre.

Ziethen’s I Corps were not ordered to march from their encampment above Bierges until after 11 a.m. when it was definite that Wellington was fighting at Waterloo and it began its march almost immediately, although it left a detachment behind to protect the wing of Thielmann’s corps in Wavre.

The 15th Brigade, leading Bulow’s Corps, stood at Chapelle St. Lambert from 10 a.m. patiently awaiting the arrival of the other brigades before approaching any nearer to the battlefield; but it was fully 2 p.m. before the 16th Brigade finally arrived and another hour before the 14th Brigade who formed the rearguard, could come up. Bulow was initially cautious because there were no sounds of battle in his front, had Wellington retreated leaving him to march on the French alone?

But all doubts were allayed at 11.30 a.m. as a tremendous cannonade announced the beginning of a great battle. At midday, after a conference with Muffling, Bulow agreed to move forward via the village of Lasne and having formed up between La Haye and Aywieres, to attack the village of Plancenoit, which lay in the right rear of the French army. But before moving, Bulow ordered forward a major scouting party to establish where exactly the French were.

At around 2 p.m. Napoleon received a long message from Grouchy with numerous intelligence reports attached. It clearly identified that three corps of the Prussian army had marched with the avowed intention of joining with Wellington’s army, but indicating that their line of march was towards Brussels, not towards Mont St Jean. This clearly indicated to Napoleon that the Prussians were not a threat that day. Lieutenant Colonel La Fresnaye, who carried this message, does not record any particular reaction by Napoleon and he remained with the Emperor for the remainder of the day.

Knowing that the other brigades were now closing up with him, Bulow, acting on the favourable reports from his scouts, decided to march the 15th Brigade to Paris wood at 2 p.m.; they found the Lasne valley boggy from the heavy rains but unguarded.

The thick Belgian mud sapped the strength of the artillery horses as the cannon sank deep in the loam and simply refused to move whilst the infantry found their boots being sucked from their feet; but with the urging of Marshal Blucher and immense determination, they finally crossed the Lasne, arriving at Paris wood at a little after 3 p.m. when pickets were placed at every exit to maintain the secrecy of their arrival. By 4 p.m. the 16th Brigade and the cavalry of the corps had also joined and another half an hour later brought the 13th Brigade up as well, having rested at Chapelle St. Lambert for some three hours. The reserve artillery and 14th Brigade arrived at Paris wood by 5 p.m. with the 5th Brigade of II Corps marching close behind.

By 16:30 however, Blucher was becoming increasingly worried about Wellington’s ability to continue to stand against the French assaults and he saw signs of troop movements that seemed to signify a withdrawal.

He ordered Bulow to launch an immediate attack with his two brigades and his cavalry without waiting for support. Bulow remonstrated, but Blucher insisted that they must do something to relieve the pressure on Wellington’s army. As Bulow’s troops went forward, pushing the French cavalry videttes back, the 13th Brigade and his corps artillery finally arrived to strengthen the attack.

Lobau was surprised by this assault on his right, but soon placed his brigades of troops and supporting artillery along a ridge of high ground to the north of Plancenoit village to face this new threat. His small corps only numbered just over 7,000 infantry and about 3,000 cavalry with which to defend against Bulow’s 30,000 men.

As Bulow advanced, he immediately sent part of the 15th Brigade out on his right to secure Frichermont and its neighbouring wood, to prevent any flank attack from Durutte’s troops. This was achieved with relative ease and the Prussians linked up with Saxe Weimar’s Nassau troops, but not without a number of ‘friendly fire’ incidents. The rest of the 15th Brigade then moved on to engage Lobau’s main force on the ridge north of Plancenoit, whilst the 13th Brigade followed them in reserve. The 16th Brigade marched forward with their artillery and the cavalry protecting their flanks, determined to take the village of Plancenoit. Possession of the village would leave Napoleon’s rear completely unprotected, making his army very vulnerable; it had to be taken at all costs.

The French cavalry videttes retired slowly in the face of Bulow’s advance and were eventually replaced by a cloud of infantry skirmishers who disputed every foot, but continued to retreat slowly until the Prussians finally reached the outskirts of the village.

This Prussian movement was also accidentally discovered by General Bernard, an aide to Napoleon, who soon reported his discovery. Eventually, around 4:30 p.m. a patrol arrived with a captured Prussian Hussar who readily revealed that the troops they could now see attacking Plancenoit were indeed Bulow’s Corps, not Grouchy.

Seeing that Lobau’s Corps on the ridge was under severe pressure and mindful that the loss of the village would spell disaster for his army, Napoleon ordered the entire Young Guard Division, commanded by Comte Duhesme to occupy it and hold it. He rushed his troops into ‘Attack columns’ and sent all eight battalions into the village. The village of Plancenoit would be fought for, to the death; here the Young Guard were determined to make a stand.

The Prussian artillery which announced the assault was heard, as intended, by Wellington. Hiller’s 16th Brigade formed line and the six battalions marched directly on Plancenoit, determined to oust the French defenders; with the 14th Brigade moving up in their rear to form a reserve. The Prussian assault was initially successful, pushing the French defenders back, as far as the open space around the church which sat on a small hillock and was surrounded by a defensive wall. Here they met a furious resistance and the advance was halted. Bloody hand to hand fighting see-sawed through the village without either side truly gaining the upper hand, although the Prussians did capture some cannon and a few hundred prisoners.

Napoleon seems to have been forced to concentrate most of his personal efforts in commanding the fight against the Prussians at this time leaving Ney to continue to apply the pressure on Wellington’s forces.

A further assault was prepared, with the 14th Brigade leading and the reformed 16th coming up in reserve. This assault reached the churchyard again and succeeded in breaching the French defences where:

…a vicious, bloody and bitter battle took place.

After intense street fighting, with little mercy being shown to the wounded by either side, the Young Guard were, in their turn, slowly evicted, forcing Lobau’s troops on the ridge to the north, to fall back slightly. Duhesme was shot in the head whilst urging his guardsmen on and unable to continue in command. He only remained on his horse with the help of a number of his officers. He was to die of his injuries at Genappe two days later.

At this moment, with Plancenoit almost fully in Prussian hands and with Pirch’s II Corps starting to arrive in support, Napoleon’s position looked very precarious indeed.

Whilst the main Prussian attack came to a moment of crisis, Ziethen’s I Corps was now also approaching the battlefield, but at quite a distance from Bulow. They marched to Ohain via Bourgeois, taking them much further to the north and delaying their arrival. However, the 1st Brigade of General Ziethen’s Corps had arrived at the valley of the Lasne brook by 5 p.m. where they remained awaiting the arrival of the 2nd Brigade.

Whilst this movement continued Lieutenant Colonel Reiche, General Ziethen’s Chief of Staff, rode onto the battlefield on Wellington’s left wing and here he met Muffling, who informed him how important it was that the Duke received early support. Reiche rode hurriedly back but could not find Ziethen and took the cavalry vanguard onto the battlefield at a canter. When only one thousand yards from the French, Ziethen’s men halted again whilst they sent forward scouts, who returned with the impression that Wellington’s army was close to defeat.

At this very moment Major von Scharnhorst of Blucher’s Staff brought an order for Ziethen’s Corps to move to their left and support Bulow’s battered forces around Plancenoit, which Ziethen felt honour bound to obey.

Muffling soon observed Ziethen’s movement and having ridden over to the Prussians to discuss the state of affairs, he persuaded the general to again march to support Wellington’s left rather than supporting his own countrymen.

The arrival of Ziethen’s troops on the left wing of his army, bolstered the weakened forces there and allowed Wellington to pull sorely needed, relatively fresh units, to bolster his severely weakened centre including Best’s and some of Vincke’s infantry and Vivian’s and Vandeleur’s light cavalry. However, it did lead to the unfortunate case of ‘friendly fire’ as the Prussian troops mistook the uniforms of the Nassau soldiers for French uniforms. When Saxe-Weimar rode swiftly over to General Ziethen to request that his men stopped firing on them, Ziethen replied sardonically:

My friend, it is not my fault that your men look like French!

Marshal Ney’s forces had only recently finally captured La Haye Sainte and he urgently requested more troops from the Emperor to exploit his success. Napoleon answered the message curtly, informing Ney that he had no troops to spare; but, ever the arch gambler, Napoleon threw the dice for one last time.

He would use the cream of his army, the Old and Middle Guard, who had stood in reserve all day, awaiting their opportunity to defeat Wellington, but first the Prussians needed to be quieted.

Two and a half battalions of the Old Guard which was all that could be spared were ordered to march directly upon Plancenoit to drive the Prussians back. The 1st Battalion 2nd Chasseurs led the charge with Major General Pelet leading them on, the 1st Battalion 2nd Grenadiers and two companies of the 2nd Battalion 1st Grenadiers following up in support. This small force, numbering no more than fifteen hundred men marched fearlessly into Plancenoit and with a great roar, pushed on through the village, mercilessly bayoneting everything in their path. Such an impetuous attack against horrendous odds should have been doomed to failure; but their fearsome reputation struck fear amongst the Prussians, and the sheer ferocity of their bayonet charges by platoon, supported by the remnants of the Young Guard, caused them to flee. They charged on through the now burning streets, recapturing the church again and driving the Prussians completely out of the village which was almost carpeted with the dead and dying of both nations.

The village was to remain in French hands for the next hour, during which Napoleon launched the remainder of his Imperial Guard against Wellington’s army in an attempt to snatch victory from the very jaws of defeat.

Rallying his men for another assault, Bulow’s troops were buoyed by the sight of fresh troops of their own, with the arrival of Pirch’s 5th Brigade commanded by Tipplskirch, which fortuitously arrived in time to supplement this next great attack.

With the Prussians now able to launch over thirty thousand infantry against less than fifteen thousand French defenders in and around Plancenoit, the eventual outcome was almost certain. Sheer weight of numbers finally overcame the French veterans and despite a stubborn resistance they were slowly forced back and for the final time the village was to change hands.

The French had no further reserves to commit against Plancenoit and the Prussians cautiously pressed on towards the Brussels highway, but were prevented from breaking through completely by the measured withdrawal, inch by inch, of the Chasseurs of the Guard.

The fight for Plancenoit had caused losses in the region of 6,000 men each.