Few had been able to get any decent rest during the incessant rain overnight, but still Wellington’s frontline troops were roused from their fitful sleep half an hour before dawn to guard against a surprise attack. Tired, frozen to the very marrow with their wet clothing clinging uncomfortably to their skin and desperately hungry, the men huddled together in their formations shivering in the bitter air as the rain continued to fall, chasing rivulets through their saturated uniforms. In front the pickets crouched, peering closely into the inky darkness and listening intently for any sound carried on the light breeze that would warn of an enemy assault, but all they heard was the occasional snorting of horses, the stifled chat of the men to their rear and the soft patter of the heavy rain splashing in the liquid Belgian mud.

Relief however was soon at hand, as to the joy of everybody it soon stopped raining, and permission was granted for men to leave the ranks in turn to obtain whatever sustenance they could procure, by purchase, or more nefarious means.

Because the Commissariat system had broken down over the last few days of rapid manoeuvring and with the supply wagons now en route for Brussels, the majority of the troops had little in their knapsacks to eat and little opportunity to replenish their food supplies honestly.

Private Thomas Jeremiah of the 23rd Foot also acknowledges that Wellington’s soldiers plundered the nearby houses as much as anyone else, despite the Duke’s fearsome reputation for maintaining discipline:

We passed on to [a] little village when we saw a wagon of flour disposed in large casks and others of these Germans were busy filling their vessels and we pushed up among the rest and commenced storing our little haversacks. You must know that our coats must be drenched with the previous days and nights rain. In the struggle to get at the casks of flower [sic] in the scuffle I tumbled into the flour cask, the flower stuck to the wet coat [&] I was as wet if not as white as a miller. When I had filled the haversacks we were yet at a loss what to mix our dough in, …water there was none in the camp, so we were nearly despairing of getting anything not only to drink but to wet the flour although there were a draw well in the yard, but it was said that the French had poisoned the water. In our way back to camp we saw a little to our left a very large gentleman’s house, we immediately made for this house, we immediately commenced our search more for something to eat than for money, but to our great mortification the house had undergone a complete ransacking and plundered of every portable article and what they could not be carried away, they smashed in pieces, so that our hopes to get something to eat was blasted. It certainly was a great pity to see the damage done to this superb mansion which was of the most exquisite taste in its architecture together with its outhouses and extensive and well laid out gardens, which formed at once a little paradise on earth. Even the fine statues that decorated the front of this house were with the turrets and obelisks as well as the beautiful fountains and cascades that had been the admiration of ages were demolished by the soldiery. ..At last we thought that there must be a cellar of wine and spirit vault belonging to this house which upon examination we found the house was well furnished with all sorts of viands & spirits. When we came to the vault door we were agreeably surprised to see the cellar filled with the choicest beverage but like everything else, this place had undergone the severe discipline of the German soldiers, a most disagreeable proof of which was there to be seen to bear testimony of the unguarded and gluttonous propensity of 2 German soldiers who after drinking so excessively as to render themselves totally insensible and laying themselves down and there slept while the wine and liquors out of about 40 or 50 pipes was flowing on them where it appears that after they had drunk all they could drink & no more they neglected to turn the key of the vessel. When we entered we approached the men we found them dead, without any mark of violence. .. Thus happily supplied with money and good provision we lost no time to proceed to our camp where we saw our remaining 4 messmates half starved. They begun to open to their eyes at the sight of such a fine cargo of flour, brandy and here we commenced to mix our flour not with water but wine and brandy.

Across the sodden fields men prepared themselves for battle; equipment was dried out, checked and rechecked. Surgeons took up residence in farmsteads just to the rear and cleared tables to form makeshift operating tables, ordered water to be collected in buckets and laid out their butchers implements, ready to tend to the numerous horrific wounds that were undoubtedly to be inflicted in the next few hours. Foraging parties went out in all directions, with many French and Allied parties foraging shoulder to shoulder with little acrimony, for death was sure to be well sated this day and this was no time for senseless killing. Other soldiers talked and laughed as they warmed themselves around the fires that had been kindled after the heavy rains had thankfully gone. Numerous women and children from the camp followers were to be seen amongst the regiments, tending to their men, not knowing if their provider would still be alive in a few hours time.

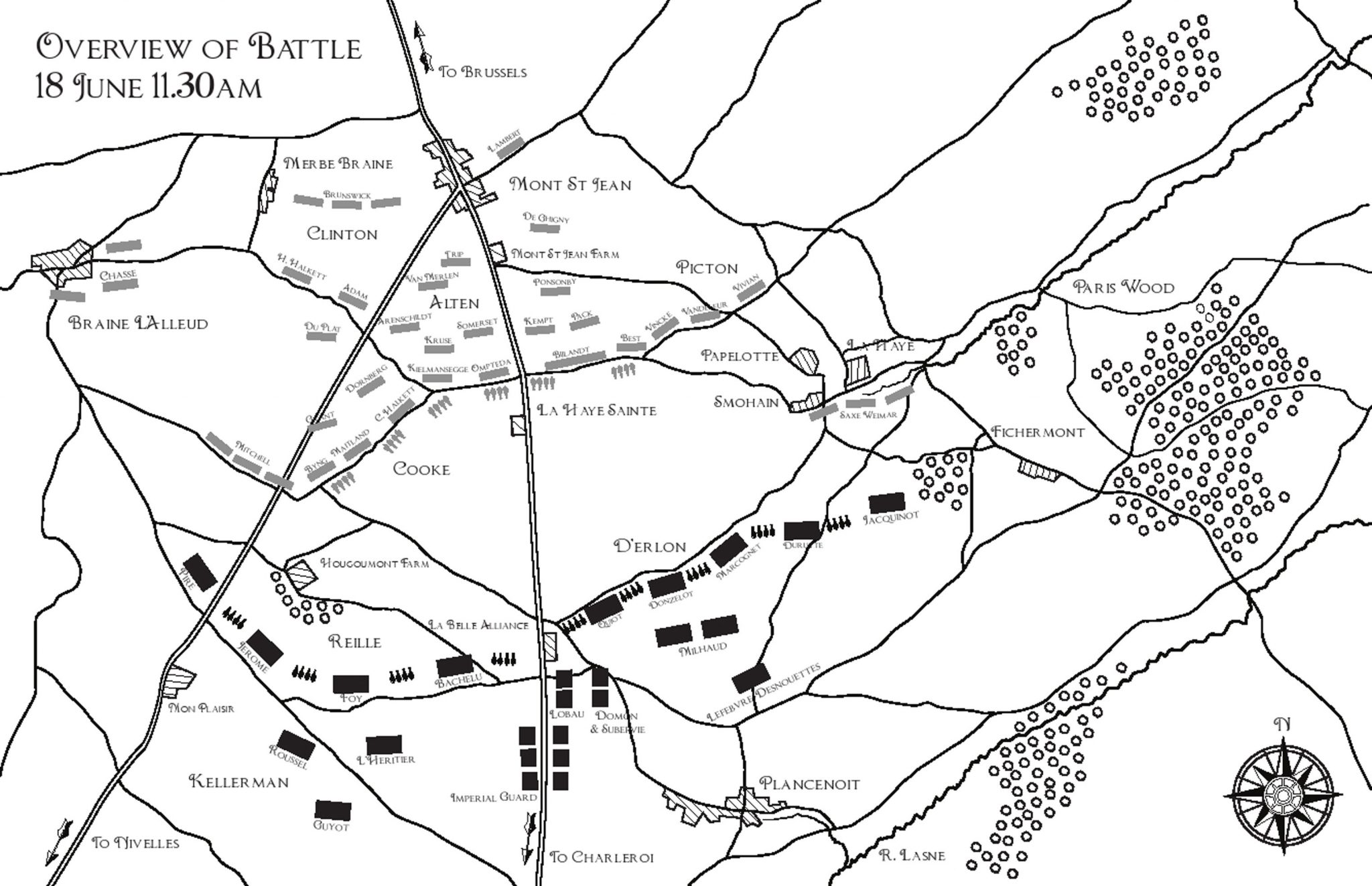

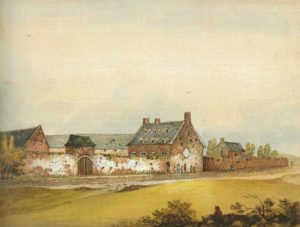

The position was dissected by the great road or chaussee, running north-south from Brussels to Charleroi and on its right, covered the main road from Nivelles which entered the position at an angle and joined the Brussels chaussee just to the north of Mont St. Jean village. Approximately five hundred metres south of Mont St. Jean farm, a low ridge ran east-west, carrying a track which ran towards Braine l’Alleud in the west and Ohain to the east. This track near the crossroads was sunken in places up to about nine feet below the general ridge height and was lined on both sides by a thick hedgerow giving some protection to defending forces and this was to form Wellington’s front line. The main strength of the position lay however in the three fortified farmsteads which stood on the front face of this low ridge, which would severely hamper any large scale attack upon the position without first taking at least one of them. In front of the western end of the ridge there lay in a hollow, the fortified chateau/farm complex of Hougoumont with its large walled gardens and extensive wood which extended towards the French lines, obscuring the view of the chateau within; directly in front of the crossroads was the smaller but eminently defensible, solidly built and high walled farm complex of La Haye Sainte; and on the eastern edge of Wellington’s position stood a number of small villages and farm complexes known as Papelotte, Frichermont and La Haye. All of these villages and farm complexes if properly manned were easily converted into minor fortresses.

The other reason that Wellington chose the position was that the ridge also allowed him to hide his troops on the reverse slope of the lower lying land to the north until they were brought forward, a much favoured and highly successful tactic he had developed throughout the five years he had fought in the Peninsula. A similar ridge only slightly higher than his own and running virtually parallel to it stood some twelve hundred yards or so south of his position. This would be an obvious point for Napoleon’s troops to form upon. Between the ridges there was a shallow valley which very deceptively undulated, making areas of ‘dead ‘ground’ and formed quite an appreciable slope running up to Wellington’s front line. To his rear there was an extensive wood, the Bois de Soignes, and Wellington has been heavily criticised by some for choosing a position from which his army would have found it very difficult to extricate itself, if they were defeated. However, the dense tree canopy restricted the undergrowth severely and there were numerous track ways through the wood and Wellington was confident that he could remove his army safely if required by holding the forest in a rearguard action. It was a battlefield of great subtlety and it proved quite perfect for Wellington’s favoured tactics.

The Duke of Wellington laid his troops out with great care behind the ridge, not only in an attempt to conceal his troops from the devastating artillery fire that Napoleon was sure to utilise, but also to leave Napoleon guessing as to where his strengths and weaknesses lay. On his extreme left wing, where Wellington expected that the Prussians would arrive quite early, just under four thousand experienced Nassau troops commanded by the Prince of Saxe Weimar held the forward posts of Frichermont, La Haye and Papelotte, with his reserve and cannon on the slope just behind. Behind the ridge, the extreme left wing was formed by the Hussars and Light Dragoons of Vivian’s and Vandeleur’s brigades. From the lane leading down to La Haye all the way across to the crossroad above La Haye Sainte was covered by Picton’s 5th Division. Running from left to right, this consisted firstly of the inexperienced militia of Vincke’s and Best’s Landwehr brigades – Best’s brigade was officially part of the 6th Division but was attached to Picton at Waterloo. The Brigades of Best and Vincke jointly formed one huge square just beyond the crest of the ridge to avoid direct cannon fire as they would have formed a very large target for the French artillery in such a cumbersome formation. To their right were the very experienced troops of Pack’s Brigade largely consisting of tough Highlanders, although they had suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Quatre Bras; and to their right were more veteran British troops under Sir James Kempt, whose right wing touched the Brussels road. This brigade included the rifle armed 1st Battalion of the 95th Rifles, who had detached much of its strength in front of the ridge; two companies taking possession of a deep sand pit which lay virtually in line across the main road with the rear kitchen garden of La Haye Sainte farm and three further companies held a small height or knoll just in front of the crossroads. In front of Kempt’s and Pack’s troops were stationed Bijlandt’s Dutch/Belgian brigade, initially on the forward slope where it was extremely vulnerable to enemy cannon fire, but moved to the ridge line before the French cannonade commenced in earnest, where it’s troops were formed in line and Kempt’s and Pack’s troops were moved one hundred yards back to form a second line. In their rear a third line was formed by the heavy cavalry of Ponsonby’s ‘Union’ brigade.

Immediately west of the main road stood Count Alten’s 3rd Division, first were Ompteda’s veteran brigade of the King’s German Legion, with Major Baring’s 2nd Light Battalion detached to garrison La Haye Sainte in its immediate front. To his right was the 1st Hanoverian brigade of Count Kielmansegge consisting of relatively inexperienced Hanoverian Field Battalions and further right again, just beyond the junction with the lane to Merbe Braine, Sir Colin Halkett’s Brigade of British infantry, much weakened after its heavy losses at Quatre Bras.

Above Hougoumont, along the ridge line stood Major General Cooke’s very strong 1st Guard Division, Maitland’s brigade to the left and Byng’s to the right and forming the corner of the British line, which now then ran to the north west, crossing the Nivelles road where Mitchell’s Brigade formed a screen supported by two squadrons of the 15th Hussars. Behind this screen General Henry Clinton’s 2nd Division was formed in reserve on Wellington’s right wing extending back as far as the villages of Merbe Braine where all the roads were blocked to form small strongholds.

The Brunswick contingent was held in reserve between Merbe Braine and Mont St Jean village, and Kruse’s Nassau troops stood behind Kielmansegge’s men. The cavalry again generally formed a third line, near the Brussels road. Somerset’s Household cavalry stood behind Ompteda and Kielmansegge and behind these stood the heavy cavalry of Trip’s Dutch Belgian brigade and Merlen’s Dutch/Belgian Light Dragoons. Behind Halkett and Cooke’s troops were the light cavalry of Grant’s British and Dornberg’s and Arenschildt’s German Legion cavalry.

Approximately one thousand yards to the west of Merbe Braine, General Chasse’s Dutch/ Belgian troops were originally detached to cover Wellington’s extended right wing at Braine l’Alleud, which General Detmer was ordered to hold to the last man.

Only fortuitously arriving just before the battle commenced, Lambert’s Brigade initially stood to the rear of Mont St Jean farmhouse near the main road as a final reserve.

But this does not account for all of Wellington’s available force that day. Seven miles to the west of the battlefield, he had deployed a significant force at a position near Hal and Tubize, to protect him from any extensive flanking move made by Napoleon’s forces. These troops consisted of two brigades of General Sir Charles Colville’s British troops and associated artillery, numbering some 6,000 men; and Prince Frederick of Orange’s whole corps of Dutch/Belgian troops numbering 10,500 men. This significant detachment shows Wellington’s fear for his right wing as it could have formed a very significant addition to his forces at Waterloo. Wellington has also been criticised for not calling them to the battlefield, where their presence would have been invaluable; but there were no good cross roads from Hal to Mont St Jean and their arrival could not have been in time to influence the battle.

To prevent rapid advances by French cavalry along the main roads, major obstructions, or abatis to give them their military term, were built from any scraps of wood or abandoned farm implements found to hand. The road from Charleroi had two, one placed near the main gate to La Haye Sainte and the other just to the north of the farm; and one was built on the Nivelles road just north of Hougoumont.

On the other side of the valley, Napoleon continued to bring his troops forward from their uncomfortably wet cantonments during the morning to form his battle formation. Napoleon had spent the night at Le Caillou as his headquarters, farmer Boucqueau being forced to retire to Plancenoit. There is clear evidence that the French Army was still deploying when the battle actually commenced and that the delay in beginning the battle was not purely to allow the artillery to manoeuvre as usually claimed. The front line on Napoleon’s right initially stretched along the track which runs from La Belle Alliance along the crest line to a point approximately five hundred yards from Papelotte. This bar come brewery was owned by one Nicolas-Antoine Delpierre who was also forced to flee. The front line was composed entirely of the infantry and artillery of d’Erlon’s still intact corps, Durutte’s 4th Division forming the right wing which was angled back to protect against a flank attack from Papelotte. Behind the infantry stood Milhaud’s Cuirassier corps and behind that stood Lefebvre-Desnouettes Guard light cavalry division including the famed 2nd (Red) Lancers. Further to the east, Jacquinot’s 1st Cavalry division looked over Frichermont, with Marbot’s 7th Hussars extended further to the east, hoping to communicate with Grouchy’s troops.

To the west the French front line was set back slightly further and followed t he crest from just south of La Belle Alliance, curving around the chateau of Hougoumont as far as its junction with the Nivelles road. From the main road passing westward the French infantry of Reille’s 2nd Corps with its attached artillery was set out in the order of Bachelu’s 5th Division, then Foy’s 9th Division and Prince Jerome’s 6th Division, their left flank being protected by Pire’s 2nd Cavalry division which stood astride the Nivelles road. To the rear of the infantry forming a second line, was the heavy cavalry of Kellerman’s 3rd Cavalry Corps and in third line the Guard Heavy Cavalry division of Guyot. Napoleon retained Lobau’s 6th corps and the entire Imperial Guard in reserve, (when it fully arrived, as the Guard was still on its march to the battlefield when it began) and these were to eventually stand astride the Brussels-Charleroi road south of the front line and stretching all of the way back to Rosomme farm. Napoleon’s dispositions showed great flexibility and retained a very powerful reserve which would enable him to support either wing as necessary or to provide sufficient punch to drive through Wellington’s previously weakened centre.

Just behind Napoleon’s left wing was a wooden tower or observatory, which was rumoured to be used by French officers during the battle to see behind Wellington’s ridge. To the right, in a hollow, was the village of Plancenoit

In all a compact battlefield, covering no more than three square miles, held Wellington’s army consisting of approximately 67,000 men with 157 cannon who faced a slightly larger French force. Napoleon’s army at Waterloo numbering some 73,000 men with a vastly superior 246 cannon.

But Wellington was happy with the delay in commencing the battle, for every hour brought the Prussian Army ever closer.

With his troops now largely in position, Napoleon finally ordered his artillery to commence firing on the allied line, his skirmishers moved rapidly forward across the valley floor to irritate and disrupt the command and control of the allied formations and the troops of all nations rapidly formed up and awaited orders whilst offering up many a silent prayer, to survive the inevitable carnage that was sure to ensue.

The cannon began to roar at half past eleven on that Sunday morning, the tremendous cannonade being heard as far away as Brussels and some even claim to have heard it in Kent. Marshal Grouchy heard it whilst on his march to Wavre; but strange to relate, by some quirk of the atmospheric conditions, the allied troops at Hal and Tubize remained blissfully unaware of the battle throughout the whole day.