The Massed Battery at Waterloo – A Review of the Evidence

One of the enduring questions from the Battle of Waterloo remains the Grand Battery placed on Napoleon’s right wing to soften up the opposition and to support the attack by Comte d’Erlon’s Corps in the first major attack of the battle. Did it actually exist? If it did, how many guns were involved? And where was the battery positioned? These questions have been argued over for two centuries and I will attempt to explain my view of these issues, utilising the latest information, but I certainly am not stupid enough to think that I will settle the argument for ever and I will as always welcome alternate views.

What is the evidence for the Grand Battery?

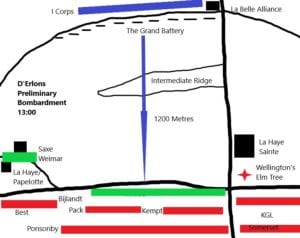

We know from his Memoirs that Napoleon ordered at 11am that the 12-pounder batteries of II and VI Corps would mass with that of the I Corps, that these 24 guns would bombard the troops holding Mont St Jean and that Comte d’Erlon would commence the attack, by first launching his left division, and when necessary, supporting it by the other divisions of the I Corps. Now, this established a battery of 18 x 12 pounders and 6 x 6 inch howitzers to batter Wellington’s line in advance of Mont St Jean , but this in itself does not establish the existence of a Grand Battery of more than fifty cannon.

Beyond this statement, we unfortunately have very few French sources for the arrangement of the cannon of I Corps during this attack, but one that does exist is of immense importance, being that of Marechal de Camp Desalles, who was no less than the commander of I Corps artillery at Waterloo and yet his statement is rarely quoted in regard to this subject. It is therefore fortunate that Andrew Field has recently brought it to prominence in his Waterloo – The French perspective.

Desalles begins by describing the orders he received soon after 11 am from the Emperor’s aide de camp Labedoyere, whilst he was in the presence of Comte d’Erlon. He records that Napoleon ‘had given me command of a battery of 80 guns’, so, we now have some evidence for a Grand Battery. This is further supported by Mauduit, who states that ‘To protect this exposed attack, ten batteries …. had been established’

The Dutch Cartographer Craan indeed shows eleven batteries on his map of Waterloo, placed at intervals along the front of I Corps, but unfortunately, they are not named.

Many of the British troops described the French preparations for the attack, although it is actually unclear how many truly had a view of the French line, given that most of the allied troops were stationed on the reverse slope. However, Captain Kincaid of the 95th Rifles was in such a position and he described in his memoirs, that ‘innumerable black specks were now seen taking post at regular distances in its front, and recognising them as so many pieces of artillery’

The length of front covered by the batteries was around 1200 metres as the frontage of an 8-gun battery was normally in the region of 90 metres, therefore it can be seen that there would have been only small gaps between each battery, as depicted by Craan. As the guns were therefore more of a congregation of individual batteries (although boosted by a number of reserve batteries) it is a moot point whether it can be called a Grand Battery. The guns were certainly massed for effect, but initially being little more than the guns lining the left wing of French army, so we can accept that there was a Grand Battery of sorts, indeed some now claim (following this argument to its full conclusion) that there was one huge Grand Battery stretching across the entire front of the French army.

How many guns were in the Grand Battery?

We know that Napoleon had supplied 24 reserve guns to the battery , whilst I corps had 4 divisional batteries totalling 24 x 6-pounders and 8 x 5.5 inch howitzers, and a horse battery of 4 x 6 pounders and 2 x 5.5 inch howitzers, giving us a total of 62 guns.

However, Desalles records that he had been given command of ‘a battery of 80 guns, which was to be composed of all my six pounder batteries, my twelve pounder reserve battery, and of the reserve batteries of the 2nd and 5th [6th] Corps which would actually give me 54 guns, of which twenty four would be twelve pounders’. He lists only 54 guns allocated to him . This discrepancy of eight guns is explained, in that he did not include Durutte’s battery, as this was (he presumably thought) was to be engaged against the Papelotte area.

Although Desalles was informed that he would have command of 80 guns, he fails to explain where the rest of the guns would have come from, perhaps indicating that they were either never allocated or at least (more likely) were not under his direct command. It would appear that a further 24 guns were allocated by Napoleon to support d’Erlon’s attack from the Guard artillery, although the specific order has not survived. These would increase the number of guns in the battery to 90 if all I Corps were available (although Desalles indicates they were not) or 82 guns if the one battery is removed as per Desalles. It is however usually stated that the Guard artillery were held in reserve near La Belle Alliance and were actually not engaged. The fact that they are not recorded as having been involved (not mentioned by Desalles) or suffered any known losses in the subsequent allied cavalry charges would tend to confirm this.

Therefore the Grand Battery would appear to have consisted of 54 guns (agreeable to Desalles statement), -Captain Leach 95th estimated it at 50 guns and another unknown officer of the 95th counted 40 – or 62 guns if Durutte’s battery is included. I choose to include all of the guns of I Corps because we know that Durutte’s division was involved in the attack on the allied ridge and only got involved in a serious attack on Papelotte later in the day , thus the associated guns were likely to have been fully involved in the barrage which commenced at about 1 pm.

Where was the Grand Battery Established?

This of the three questions seems to be the most contentious of all, with William Siborne and a number of modern historians (including Mark Adkin, Nick Lipscombe and John Hussey) opting for its deployment on an intermediate ridge some 400 metres in front of the main French front line, which ran along the lane running from La Belle Alliance towards La Haye and was between 1,000-1,200 metres from the allied ridge.

This premise has gained a great deal of credence in recent times because of the ideal range of French artillery of the period. Kevin Kiley and Stephen Summerfield have both shown that French cannon of 1815 had an ideal range (without any elevation) of 600-800 metres, depending on whether a 6-pounder or 12 -pounder. This would mean that the French artillery would seek to engage their enemy with aimed fire at no more that 700 metres and this would make the interim ridge almost perfectly placed on which to establish the Grand Battery.

But, was the battery initially organised for aimed fire? In fact, the evidence is very clear that it was not. Wellington’s troops were placed behind the crest of the ridge, with only skirmishers and the allied artillery obviously dotted on the ridge crest. Engaging such small individual targets was usually deemed a complete waste of time and effort and would have failed signally to soften up the allied defences in advance of d’Erlon’s attack. The task allocated to the Grand Battery was therefore to drop cannonballs and shells into the ‘blind area’ behind the allied crest, to destroy the allied formations undoubtedly stationed behind the ridge in close proximity to the guns on the crest. Their target was therefore an extensive area stretching 1000 metres along the allied ridge and extending back some 4-500 metres behind, where the allied forces were sure to be sited in depth. With the need to drop shot over a crest, rather than fire horizontally, the barrel would be elevated. A 1 degree elevation of the barrel would increase the range of the first bounce to 900-1,000 metres and 2 degrees elevation to 12-1400 metres, when we suddenly find that the main French line on the lane near La Belle Alliance is no longer too distant. In fact at 2 degrees elevation the maximum range of the guns was near 2,000 metres. If it is argued that fire from this distance was ineffectual and a waste of ammunition as claimed by supporters of the intermediate ridge, then we must accept that all of the cannon ranged in front of II Corps who engaged the allied line at similar ranges were wasting their time – something that the allied troops positioned on this wing, would undoubtedly hotly contest!

What do the eye witnesses state?

Our first port of call must be Desalles, who states ‘First I ordered all these guns to be put in battery on the position we now occupied, mid-slope [ie just in front of the infantry on the Belle Alliance track], in a single line and began firing all at once to astonish and shake the morale of the enemy’. Desalles states that the 3 x 12 pounder batteries were on the left, the three divisional batteries (minus Durutte) in the middle with their divisions and the horse battery on the right – he should know. Bro actually places the 12 pounders were in the middle and the divisional guns on the left , but he cannot be such a reliable witness, being in the cavalry.

Sergeant Canler of the 28er Ligne states that the battery was on the plateau of Belle Alliance, whilst Mauduit states that the batteries were established ‘on the mounds to the right of La Belle Alliance to the front of the divisions of I Corps’. Beyond this, there are no other specific statements from the French as to where the guns were sited, but as the only three we have all confirm that the guns were placed on the slope just in front of the I corps it would seem conclusive.

It must be stated that one allied witness claims that 74 guns were established on the intermediate ridge, this is Shaw-Kennedy, who is deemed a reliable witness, but he wrote many years after the event and is a lone claimant and was not personally involved in the action on the left wing. We know some guns were established there at some stage, and Shaw does not say when they got there, so the only real discrepancy in his account is the number of guns in the position. Sergeant Cotton also places the French guns on this ridge, but he can hardly be viewed as an eyewitness, his situation at the battle giving him no opportunity to see it for himself.

This would also answer two other problems regarding the placing of the guns so far forward, even raised by Mark Adkin, who is an advocate of the intermediate ridge as the site of the battery from the commencement of the action.

The first is the vulnerability of the guns on such an advanced position without any infantry or cavalry support, at the mercy of the allied cavalry. It has been argued that the French guns commanded by Senarmont at the Battle of Friedland had advanced alone to less than 200 metres from the Russian infantry, but in this example the enemy was formed in columns in the open and highly visible, the French infantry were close by, desperately trying to close up with the guns and could be seen by the Russians, Senarmont’s guns fired and moved by section thereby maintaining a constant and severe fire on the Russians, destroying all hope of forming a counter attack on the guns – none of which can be deemed appropriate to the position the French artillery found at Waterloo. Indeed, Desalles states that Ruty (overall commander of the artillery) ordered the guns to move onto the forward ridge, but Desalles discussed with Ney the dangers of attack by allied cavalry on the forward ridge and delayed the movement.

It is also clear that such a large battery ranged along the intermediate slope, would have had a huge number of caissons, horse teams and other paraphernalia drawn up in the hollow behind. All of this would have formed a massive obstruction for the infantry when they advanced. We are asked to believe that the troops formed into columns on the trackway near La Belle Alliance marched forward a few hundred yards, then filed singly through the gun line (all eighteen thousand men!) which would also have forced the guns to stop firing. They then reformed in front of the guns (the guns opening up again as the infantry moved lower down the slope) and then advanced on the allied position? I think not! No soldier on either side mention such a cumbersome and unmilitary set of manoeuvres, and Wellington (& Uxbridge) watched the French infantry perform this mess-up without seeing the opportunity of launching his cavalry whilst the French infantry were completely unformed and preventing the guns from operating. Surely the answer is that this never happened and not one interestingly not French eyewitness claims that it did.

Few of the allied troops were in a position to view the French batteries, but a few allied officers made statements. Lieutenant James Hope of the 92nd states that ‘About one o’clock, he (Napoleon) opened a most handsome fire upon our division from numerous artillery planted along the ridge on which his army was posted. Under cover of this cannonade, he pushed forward three columns of infantry.’ Whilst, Lieutenant Gunning of the Royal Dragoons, recalled the advance of d’Erlon’s troops and that ‘At 3 pm [sic], they advance steadily, as if at a review, covered by guns on their own left, that kept up a continued fire on our brigade’ . George Simmons 95th recalled watching the infantry form up but does not mention any movement from the French guns. These would all appear to confirm that the battery was on the main French ridge and continued to fire from there whilst d’Erlon’s troops advanced.

But further, such a huge battery of up to eighty guns, would not only have been a huge target for the allied cavalry, but would also have proven a major impediment to them in their advance, forcing them to pass around or through the guns. So what do the allied cavalry remember of cannon during their charge forward? The Scots Greys and the left wing of the Royals were struck by cannon fire as they crested the allied ridge, but where these guns were positioned is not made clear. Joseph Stratton states that ‘I am inclined to think that the artillery by which our left was annoyed, must have been placed on the opposite heights. We do not recollect coming on any guns accompanying the French column…’ Whilst Lt Colonel Wyndham records that [Paymaster] Crawford tells me that after this, they [the Greys] went up the high ground and took the guns, somewhere about 20’. Clark Kennedy of the 1st Royal Dragoons appears to indicate that the cavalry rode across the entire valley towards the guns, stating that ‘we continued to proceed on… getting under the fire of fresh troops stationed on the opposite height’. Yet again Regimental Sergeant Major Thomas Barlow of the Royals stated that ‘The enemy cavalry ran away and we pursued them for about half a mile’ , he also fails to mention passing any guns. Lieutenant Samuel Waymouth’s map of the action shows the positioning of the cuirassiers and red lancers [whether he identified them correctly is another debate] south of the intermediate ridge but does not indicate any French battery and does not indicate in his version of events that any guns obstructed their ride. Cornet Gape of the Scots Greys states that when down in the valley before their charge ‘we were just in the range of the 12 pounders…’ which could be read as at ‘extreme range’. None of these statements are categoric proof, but they do all seem to indicate that they were only bothered by serious artillery fire on the left, and that they did not encounter French guns in their charge until they got to the main ridge. This again would appear to dispel the notion of an eighty-gun battery along the intermediate ridge on two counts, firstly that they are not struck by heavy cannon fire from the front and secondly, that they did not encounter any guns whilst riding forward over this ridge and beyond.

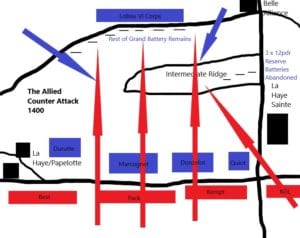

In fact, Desalles confirms this scenario, as he says that he planned to move forward during the enforced lull in their firing as the infantry reached the allied crest, in series (battery by battery) to the forward ridge thus maintaining a high level of fire (if required in support) throughout, but his plans were apparently thwarted by Lt Colonel Bobillier who commanded the three 12-pounder batteries, whom he saw ‘move off with the reserves and go, without any precautions, to the second position [the intermediate ridge]’.

Desalles states further, that the reserve batteries arrived on the intermediate ridge and began to deploy, that he then sent his adc to order the other guns forward in support, but suddenly the French infantry were broken and pursued by the allied cavalry. ‘They arrived all mixed together with the enemy on the reserve artillery [on the intermediate ridge] whose fire was paralysed by the fear of killing their own men’. Desalles tried to rescue his own reserve battery and brought it into action but it was eventually overrun. The divisional guns do not appear to have had time to move forward at all, or perhaps a few had started to move, and these guns still firing from the main French position would have been the guns that were attacked by the allied cavalry (Greys, Inniskillings and Royals) who reached the guns on this ridge and were subsequently surrounded by the sweeping flank attack of the lancers whilst on the French slope.

The scenario painted by Desalles, where only the three batteries of the reserve artillery reached the left of the intermediate ridge is surprisingly confirmed by an allied witness. De Lacy Evans records that during the cavalry charge ‘we ascended the first ridge occupied by the enemy, and passed several French cannon, on our right hand, towards the road, abandoned’.

This also fits the scenario set by the Royals, who had suffered like everyone else during the initial bombardment, but only received cannon fire from the left as they passed over the ridge line. The guns on their left (French right) being the divisional guns of d’Erlon’s corps who remained in position firing whereas the guns on their right (French left) we know were in transit at the commencement of this attack by Ponsonby’s horsemen and were effectively out of action.

Confirmation of the fact that the cavalry rode right up the main French line to reach the guns comes from Lieutenant John Hibbert of the 1st Royal Dragoons, who states that having engaged with the French infantry and guns on the ridge ‘they saw their mistake too late, and a few (this is about half the regiment) turned and rode back again; no sooner had they got about five hundred yards from the French infantry than they were met by an immense body of lancers…The Greys I believe, acted in the same manner and of course got off as badly as we did.’ Five hundred yards from the intermediate ridge would have put the lancers on the slope of the allied ridge where we know the rocket troop and infantry were now deployed. It must mean that the guns were on the main ridge.

It would therefore appear from virtually all of the available evidence, that there was a Grand Battery and that it principally consisted of 62 guns (possibly joined by some Guard units), it was initially formed on the main French ridge just in front of the French infantry and that it was intended to move them forward to the intermediate ridge, but because of the allied cavalry attack only the three 12 pounder batteries ever reached there and deployed. These were the guns described as abandoned there. But the allied cavalry of Ponsonby’s Brigade (particularly the Greys) must have pursued further towards the original French front line (the 85er Ligne were left there by Durutte to protect his divisional guns and record having to fire on allied cavalry) and these were the allied cavalry who were surrounded by the French counterattack including Bro’s lancers.

I believe that this scenario completely ties with the evidence provided from both sides and hopefully ends the speculation regarding the Grand Battery being sited on the intermediate ridge, but I doubt it!