With the Prussians now threatening his flank, Napoleon was forced into making a straight choice between retiring to fight another day and pressing on to force a decision. Withdrawal was uncertain, with his troops already agitated and suspicious of treachery, they might simply rout; Wellington and Blucher were also sure to press their advantage and he might conceivably be pushed all the way to Paris. The only other alternative was to continue fighting, to hold one adversary in check and to launch an all out attack on the other, to break them. Napoleon, ever the arch gambler, decided that attack was the best strategy and ordered his Guard to spearhead a decisive attack on Wellington’s line, intending to smash through his sorely weakened centre, whilst holding Blucher at Plancenoit.

Messengers were sent along the French line bellowing out the wonderful news that the heavy cannonade on their right announced the arrival of Marshal Grouchy and his troops; and that with this reinforcement of over thirty thousand men Wellington’s army was doomed! Buoyed with the news, Napoleon’s troops surged forward with renewed hope and belief. As Marshal Ney recorded :

About seven o’clock in the evening, after the most frightful carnage which I have ever witnessed, General Labedoyere came to me with a message from the Emperor, that Marshal Grouchy had arrived on our right and attacked the left of the English and Prussians united. This General Officer, in riding along the lines, spread this intelligence among the soldiers, whose courage and devotion remained unshaken, and who gave new proofs of them at that moment, in spite of the fatigue which they experienced.

The Young Guard, numbering some four thousand five hundred men under Comte Duhesme and two and a half battalions of the Old Guard numbering just over one thousand five hundred men, had already been committed to the defence of Plancenoit. Therefore, Napoleon only had eleven battalions of the Old and Middle Guard left to utilise. He chose to commit ten fresh battalions of the Guard to this attack, leaving just the 1st Battalion 1st Chasseurs at his headquarters at La Caillou and the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Grenadiers near La Belle Alliance as a reserve, the majority of the 1st Battalion soon joining it having returned from its successful intervention at Plancenoit.

As the ten battalions marched forward into the shallow valley, they were accompanied by units of Guard artillery and Guard cavalry on its wings. Meanwhile a concerted advance by the remnants of the infantry of both Reille and d’Erlon fully supported this movement, adding greatly to the pressure on Wellington’s line.

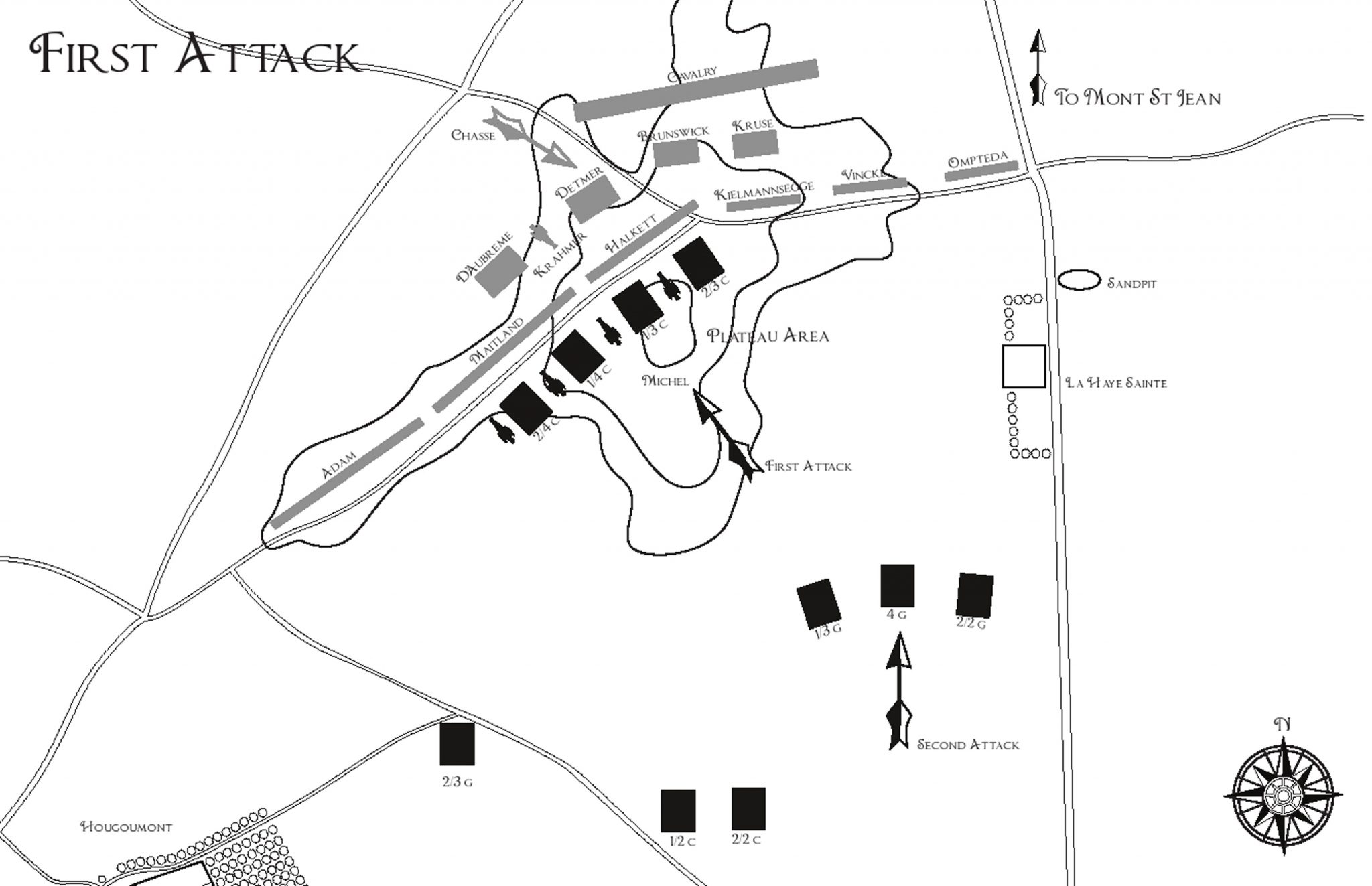

But the Duke of Wellington was not unaware of this new threat, as a French officer had just crossed into the lines proclaiming for his King and informing everyone that Napoleon’s Guard was about to attack. Armed with this crucial information, Wellington was not slow to react and orders were soon rushed along the line for units to form in an unusual four deep formation, which would give solidity against cavalry, but would drastically reduce the firepower and frontage of each battalion. Because of this reduced frontage, Halkett’s and Maitland’s men closed up to the left and Clinton’s troops moved forward to fill the void above Hougoumont. Troops had also been brought across from the left wing as the Prussian presence here had diverted French attention and not only Vivian’s and Vandeleur’s light cavalry, but also Vincke’s Hanoverian infantry had moved to bolster the area manned by Kielmansegge’s exhausted men. Pack’s Brigade, minus the 1st Foot which remained in the front line, was also moved nearer the crossroads and formed up as a reserve to Kempt’s and Lambert’s Brigades. But more men were needed, and Chasse’s Dutch troops were brought up from Merbe Braine to stand just behind the front, Kruse’s Nassau Reserve was also brought into the front line. Everyone on the allied ridge knew that this was critical moment and that they must hold the line at all costs.

The French cannonade rose to a new crescendo and the light infantry of Reille’s Corps swarmed up the ridge to disrupt the allied line as the Guards marched forward purposefully to serve the coup de grace. The Emperor himself initially rode at the head of his Guards, accompanied by Marshal Ney, across the floor of the valley, before his aides insisted that Napoleon should proceed no further as he might be killed. Perhaps such a heroic death was what Napoleon really desired at this point, but sanity regained the upper hand and he turned reluctantly aside to wave on his veteran troops as they began the slow march up the incline towards the allied line. With drums beating as hard as the drummer boys could manage and with the shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur’ constantly on the wind, they drove on for the ridge in square formation without skirmishers, seemingly oblivious to the shot and shell that rained upon them from every allied battery still able to bring their cannon to bear upon them. However, the allied guns were now getting low on ready ammunition or had completely exhausted their stocks and retired. It seems that the rate of fire soon slowed, which gave confidence to the Guards as they marched towards them.

This attack, as described by both allied and French sources was carried out in waves, or three separate disconnected attacks caused by delays in units arriving.

The first assault was made by the four battalions of the 3rd and 4th Chasseurs with supporting artillery who had proceeded without waiting for the other Guard battalions to form up.

As the French Guards neared the ridge line, the rear battalions in the column deployed to right and left and they made the final approach as four parallel battalion columns or squares in the order from the left of 2nd Battalion then 1st Battalion 4th Chasseurs, the1st Battalion and then 2nd Battalion 3rd Chasseurs. Their right actually reached the crest around the plateau area now crowned by the lion mound and they stretched out to the left of it. Here they could see the allied artillery hurriedly withdrawing and only a shaky line of British infantry commanded by Halkett in their front; indeed Lloyd’s artillery was caught before they could move and were overrun. This was the moment to push on and achieve a stunning victory, but they did not. As the Imperial Guard appeared on the crest, Maitland, who had previously ordered his British Guards to lie down to avoid the cannon fire, made them stand; this sudden appearance of the British Guards undoubtedly contributed to their decision to halt and deploy. They stood on the crest, probably awaiting the other battalions to arrive and commenced a heavy fire-fight. The 3rd Chasseurs facing Halkett’s depleted brigade appears to have had the better of this exchange of musket fire and the British infantry were thrown into confusion, forcing them to slowly give ground; but the 4th Chasseurs had marched straight into the relatively fresh 1st Foot Guards, whose firepower greatly exceeded that of the French and their wings, which extended beyond the French, inclined inwards to fire upon their flanks.

Captain James Nixon of the 1st Foot Guards records:

…the head of an immense column appeared trampling down the cornfields in our front, advancing to within a hundred and fifty yards of us, without deploying or firing a shot. Our wings immediately threw themselves forward and kept up such a murderous fire, that the Imperial Guard retired losing half their numbers, who without exaggeration absolutely lay in sections.

Witnesses all seem to agree that the fire from the British Guards and Halkett’s men added to the fire from Krahmer’s cannon which had just deployed on Halkett’s right, having been sent forward by Chasse, rapidly destroyed the head of these squares and all of their commanders were hit. Within minutes General Michel commanding the Chasseur Division was killed, Colonel Malet of 3rd Chasseurs was mortally wounded, with battalion commanders Cardinal and Agnes dead and Angelet wounded. Many witnesses speak of up to two hundred casualties within the first minutes. A British ‘Hurrah’ followed by a swift bayonet charge proved too much. The 4th Chasseurs fled with the British guards in pursuit. Having witnessed their demise, the 3rd Chasseurs withdrew as well.

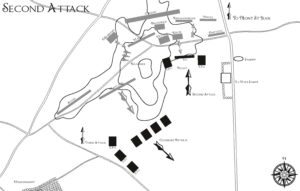

But, just as this attack failed, the second wave arrived on the ridge line to their right. This consisted of three battalions of Grenadiers which had chosen to march to the right of the first attack, presumably to join alongside them. The 1st Battalion 3rd Grenadiers were on the left and to their right were the single battalion 4th Grenadiers and the 2nd Battalion 2nd Grenadiers, formed in l’ordre mixed, with the wing battalions in column and the centre battalion in a line two companies wide, or column of divisions. This attack struck Wellington’s line exactly at its weakest point, to the right of the lion mound. Here Halkett’s men and Kielmansegge’s landwehr troops were already buckling, and this attack, added to severe ammunition shortages, soon forced the latter to retire to the edge of the battlefield leaving a significant gap in the line. Here Kielmansegge managed to rally most of his troops and he was eventually able to lead them forward again, but only after this attack had ended. Vincke’s two battalions of fresh Landwehr troops of Giffhorn and Hameln stood a little longer but were eventually forced to retire slowly from the onslaught of the Grenadiers. The Guard were accompanied by cannon, which cleared swathes through their squares with each awful discharge of grape at no more than one hundred yards distance. An attempt to send two companies of the Giffhorn battalion in line to drive off the artillery was only too quickly destroyed by the Guard cavalry that hung on the flanks of the artillery. To their rear, Vincke’s other two battalions, of Hildesheim and Peine were also caught up in this general movement to the rear, retreating from the relative safety of Mont St Jean and marching for Brussels, but they were stopped by Lieutenant Colonel Scovell, who ordered them on his own authority to return to the battlefield, which they did, but they only arrived to find the battle at an end. Kruse’s Nassau troops also reeled under the heavy fire, until the Prince of Orange rode forward and ordered these troops to charge with him. The Nassau troops were unsure, but with the prince at their head they pushed forward with some determination; but only a small setback was likely to derail their attack and it was not long in coming. Suddenly the Prince of Orange, their talisman, slumped in his saddle as he was hit in the shoulder by a shot. He dismounted, but was helped back onto his horse and was quickly escorted to the rear. The whole regiment retired rapidly after him. Things looked extremely serious at this point and for once the Duke of Wellington was not in the immediate vicinity to sort things out, at this moment being with the Guards. Vivian’s light cavalry and the remnants of the heavy cavalry formed a thin line in the immediate rear of the wavering Germans and forced them with the back of their sword blades to return to their ranks and to continue to stand.

The moment required firm will and determination and the allies were lucky enough to have such a man right on the spot, General Chasse with his Dutch Division. Initially having moved up from Merbe Braine, he had been placed in second line in support; however, Chasse quickly recognised that the units in his front were giving way and that shortly he was very likely to be called upon to plug the gap in the line. Initially he had sent forward Krahmer’s battery of six 6-pounders and two howitzers, which entered the line, taking a position on Halkett’s right, near Mercer’s battery. Three battalions of Detmer’s 1st Brigade were moved into the front line to the left of Halkett, where Kielmansegge’s men had stood, then, realising the severity of the situation Chasse quickly ordered the three remaining battalions of his brigade to join them. D’Aubreme’s 2nd Brigade remained in reserve in second line as did his brigade artillery under Captain Lux, who appears not to have fired a shot during the entire battle. Krahmer’s guns now unleashed a furious fire of canister upon these new French columns, literally blowing away whole files with each discharge, and halting the French advance in its tracks. These veteran Grenadiers were not to be defeated so easily, however, and both sides continued a fire fight whilst vying for supremacy. Meanwhile, Chasse had finally formed up his 1st Brigade under Colonel Detmer in a line of six battalion columns and ordering the drummers to beat the ‘storm charge’ a great roar bellowed out from his troops as they drove forward at the double in one great bayonet charge. The French Grenadiers had seen enough and they quickly retired down the slope in some disarray.

Marshal Ney who accompanied the Grenadiers attack reputedly lost three horses in quick succession, but he continued his charmed life. General Friant, who commanded the Grenadier division fell wounded, as did Baron Poret de Morvan, Major Guillemin and Baron d’Harlet.

At virtually the same time that the second wave arrived on the ridge, the leading element of the third attack also reached the allied crest, indeed so close were their arrivals that many witnesses describe it as one large coordinated attack. This final assault formed by the remaining three battalions, had approached the same area of the allied line as the first attack had, with the initial intention of acting as a

reserve to exploit any breakthrough. The British 1st Foot Guards had descended from the ridge and their formation rapidly lost shape and cohesion as they pursued the retreating Chasseurs with the bayonet. Suddenly, the British Guardsmen were brought up abruptly by the appearance of the leading element of this third attack looming out of the smoke and approaching rapidly at the ‘pas de charge’. The 2nd Battalion of the 3rd Grenadiers spearheaded this advance on the extreme left and nearly reached the plateau of the ridge line, where the British Guards showed their discipline and fell in with speed to commence a fierce fire-fight with the this new column, which soon halted their progress. Seeing that the leading element of the formation was in need of support, the 2nd Battalion 1st Chasseurs and 2nd Battalion 2nd Chasseurs began to march rapidly up the ridge behind the Grenadiers, the Chasseurs also pushing forward a screen of skirmishers, the only French Guard formation to do so that day. This movement was supported by troops of Foy’s and Bachelu’s divisions which also advanced onto the lower slopes.

Seeing the advance of this large column, Colonel John Colborne commanding the 52nd Foot, realised that the moment of crisis was at hand; he ordered the wounded to be left and in an audacious move, he ordered his regiment (a very strong battalion with over one thousand men in its ranks and still strengthened by a rich vein of veterans who had fought with much renown throughout the Peninsular War) to wheel up against the flank of the approaching columns. Seeing the 52nd Regiment manoeuvre to position their line parallel with the long flank of the Guard column, Major General Adam, ordered the other units of his brigade to support this movement on either flank, something that the 71st initially struggled to do, their colonel misjudging the situation and ordering his battalion to face about, a movement usually made before retiring.

Once in position the 52nd marched rapidly across the face of the slope, well below the ridge line, upon the column of Chasseurs and troops of Bachelu’s and Foy’s Divisions which had been ordered to support the Guard attacks. As they approached, they fired a series of

crashing volleys which crushed the column. It stopped and after a short lived attempt to return fire, they simply crumpled and ran as the 52nd charged on with the bayonet. The second and third attacks had both broken and all along the French line the cry of consternation was to be heard ‘La Garde Recule!’ [The Guard Retreats].