Whilst the attack developed against Hougoumont on his right, the troops of Wellington’s left became acutely aware of a great movement of troops on their front and it was not long before they became convinced that they would soon have to defend themselves against a major attack of their own.

But soon it became obvious that the French were preparing a great attack on Wellington’s left wing and a great number of guns were added to the position along the French ridge running towards Papelotte, as they prepared to put down a massive barrage to soften up the allied defences. The slow deliberate formation of these various batteries was watched with great trepidation by the few allied troops who could actually see what was being prepared for them.

By 1:30 p.m. some sixty two guns, consisting of forty six cannon – most of which were only 6 pounders – and sixteen howitzers, had by now been brought into the line and the dreaded signal was finally given for the guns to fire in one concerted salvo, followed by a continuous barrage, worse than any veteran in the allied ranks had ever faced before.

The French gunners were only presented with the allied artillery batteries sprinkled along the crest as a meagre target – who were forbidden by Wellington to engage in counter battery fire – and a scattering of skirmishers dotted along the face of the ridge. Most of the shots expended on these difficult targets missed and they simply buried themselves into the soft earth of the ridge or flew high over the crest to plough short furrows in the unseen fields beyond. These shots did however unwittingly cause some losses to the troops hidden behind the crest, where the allied troops had to endure the occasional solid iron cannon ball smashing through flesh and bone, fully capable of cutting a man in two or destroying a head arm or leg of either soldier or horse, often leaving no more than an unrecognisable mass of gore where they had just stood. Simply calmly sitting or lying waiting patiently for death to call sorely tested the nerves of both novice and veteran, it was worse when not doing anything. Such sights sapped morale as they felt impotent in the face of it.

This barrage was purely designed by Napoleon to soften up the area around the crossroads in preparation for a mass infantry attack, supported by cavalry, aiming to drive a wedge through Wellington’s centre and to capture and hold the farm complex of Mont St Jean.

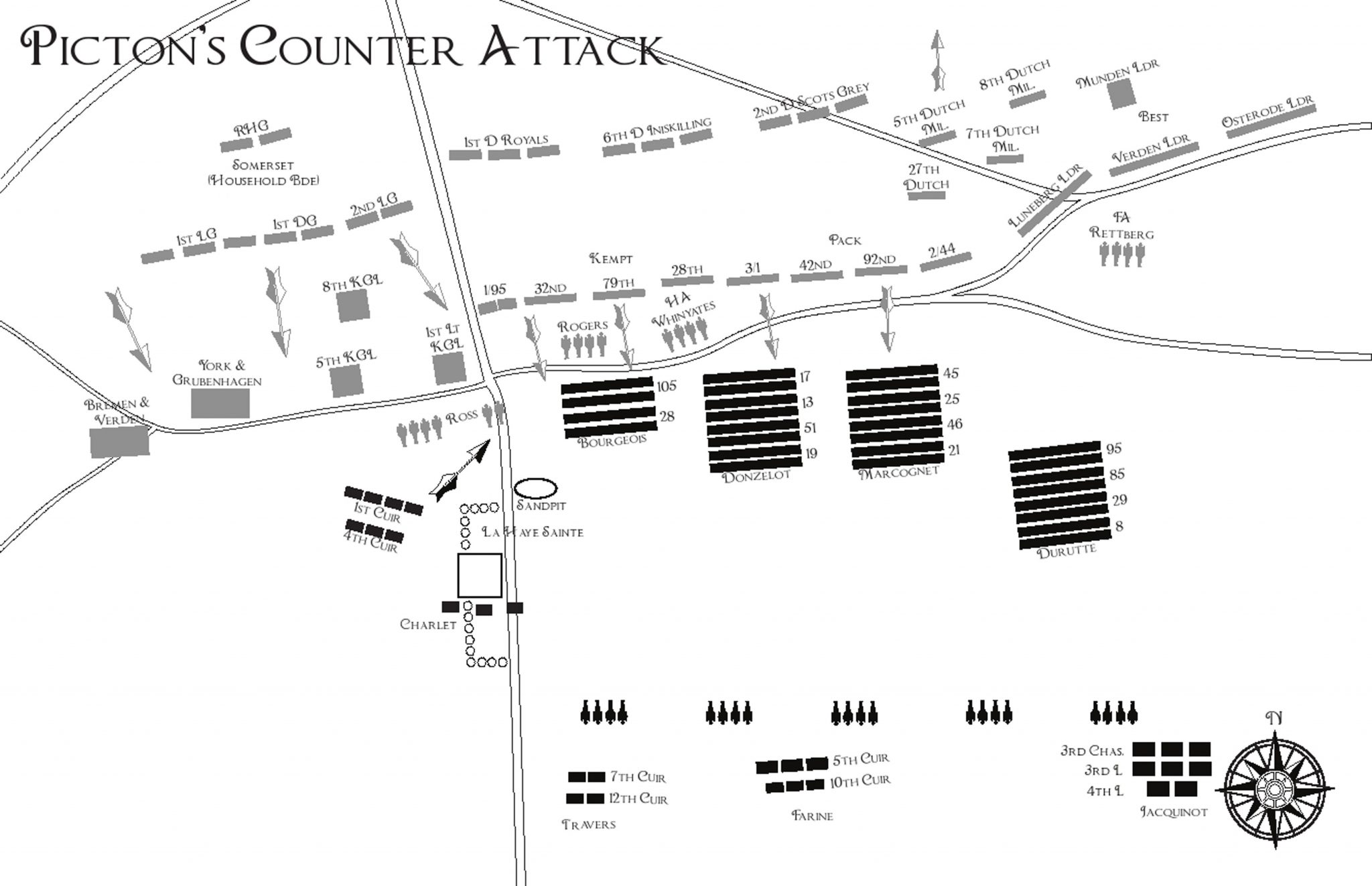

The order for d’Erlon’s corps to begin its advance towards the allied ridge came at about 2 p.m. The four divisions of d’Erlon’s 1st Corps were arrayed in battle order from the Brussels chaussee all the way along the ridge to the edge of the valley running into Papelotte. On the left stood Quiot’s Division (4,200 men); to their right Donzelot’s Division (5,250 men); then Marcognet’s Division (4,200 men) and finally Durutte’s Division (4,000 men) formed the right wing. The left of the corps was protected by Dubois’ Cuirassier Brigade (780 men) and their right by Jacquinot’s Chasseur and Lancer Brigade (1,700 men).

Donzelot and Marcognet’s divisions formed the centre and would simply drive straight ahead, but the two wing divisions were threatened by the allied troops garrisoning the outposts of La Haye Sainte and Papelotte. On the left, Charlet’s Brigade was to launch an assault upon La Haye Sainte, whilst Bourgeois’ Brigade marched upon the area around the sand pit. Durutte’s Division however would advance entire towards the ridge on the right.

It took quite some time to deploy this mass of nearly eighteen thousand infantry, not helped by the accurate fire of the allied artillery who now concentrated all of their firepower on these great masses of troops as they began to advance.

The deployment chosen was also unusual for such an assault. It was usual for the French to attack in battalion or regimental columns, but against solid infantry deployed in line this basic formation was liable to be defeated by overwhelming firepower; to counteract this, the formation used would be ‘l’ordre mixed’, whereby one or two battalions in line were bolstered on either flank by a further battalion in column, thus increasing their firepower whilst retaining the strength of the formation, but slowing them down and making the formation more cumbersome.

However on this occasion Ney and d’Erlon had chosen quite a different formation, ‘column battalions by division’. Each of the eight battalions of a division were placed in line, each battalion line was placed only a few paces behind each other and so formed a wide but quite narrow column; which served to increase firepower, reduce the column depth – therefore reducing its vulnerability to cannon fire – but also retained some solidity. The columns had a front of 140 to 150 men each, with a depth of 24 ranks. With such dense formations (the two main columns covered the size of football pitches) there were a number of drawbacks; there were spaces of up to 200 metres between each division making a coordinated attack difficult and their only defence against cavalry would be to form a solid mass, which relied on all of the battalions understanding their role in forming such an unusual formation. It was also virtually impossible for any of the battalions to change formation, it was completely inflexible. The divisional artillery would also move up with the columns.

d’Erlon led his troops from the front on horseback as they marched toward the allied ridge with a thick cloud of light infantry pushed out in front. The drummers continually beat the ‘Pas de Charge’ as they trudged the thousand yards to the ridge line in front, their officers and men encouraging themselves with constant shouts of ‘En Avant’ and great cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’

The columns advanced ‘en echelon’ with the left column in front, therefore each mass to the right was set back slightly so that they would arrive at the allied crest in a successive wave of attacks, designed to slowly overwhelm the defending troops. The allied artillery – although few in number on the left – poured a very destructive fire

upon the unwieldy formations; cannon balls forced lanes through the serried ranks and shrapnel tore gaping holes in them. The French batteries were forced to cease firing as the French columns began the slow climb up the ridge. The allied artillery could now be joined by formed infantry who lined the ridge crest, fully prepared to meet the French attack.

As the left hand column under Bourgeois approached the sand pit it was stung hard by the intense crossfire not only from the 95th Rifles who lined the sand pit and the knoll further behind, but also from the defenders of La Haye Sainte and even from a few companies of the 1st Light Battalion K.G.L. who had crossed the chaussee to fire into the flank of the advancing column, destroying its leadership. Such an intense fire forced the column to veer to its right to pass up the side of the sand pit; but it did not stop its determination to crest the ridge and the riflemen of the 95th in the sandpit were forced to withdraw at speed to rejoin the rest of their battalion. The column now approached the crest in front of the right wing of Bijlandt’s Dutch/Belgian Brigade, which had already suffered greatly during the fighting at Quatre Bras – losing a quarter of its men – and now lined the hedgerow in front of Kempt’s and Pack’s British Brigades. The French were encouraged to note that a battery of guns in their front was being hastily removed as they approached. The morale of the Dutch/Belgian infantry broke, they turned and fled through Kempt’s troops; some fled as far as the forest, but a number simply ran to the rear and their officers did eventually reform them, to join in the allied counterattack.

Kempt could see that the Dutch/ Belgian infantrymen were fleeing and ordered his three regiments to stand up, to form line and advance up to the crest line. The contending soldiers would not have known what was fast approaching on the opposite side of the ridge, but just as Bourgeois’ column reached the hedge and dared to imagine that the guns of Roger’s battery[8] in their front were in their grasp and that victory was to be theirs; but their front ranks stopped at the sight of three British battalions approaching them with great determination in line. A ragged volley by the French was met by a crashing volley from the British line which overlapped the column’s flanks, it was followed rapidly by a great cheer and the British infantry charged forward with the bayonet. Immediately after ordering the charge, General Thomas Picton was struck by a musket ball in the centre of his temple, killing him instantly.

Confusion reigned within the French column, numbers at the head had been struck down by the awful volley, and the ranks which followed became confused as some brave souls prepared to cross bayonets, whilst other sought to turn back, only to be forced on by the rear ranks who had little knowledge of what was happening in their front. Close hand to hand fighting broke out and one hardy French officer grappled for the Colours of the 32nd Foot but was run through by Sergeant Switzer’s pike & the sword of Ensign John Birtwhistle. However, eventually Bourgeois’ men began to recoil from the bayonet charge and began to retire slowly back down off the crest.

But the allied cry of ‘cavalry!’ announced the arrival of Dubois’ Cuirassiers, who had flanked the march of Bourgeois’ column and had already destroyed the Luneburg Battalion. Having moved up the western face of La Haye Sainte under intense rifle fire, they had found themselves faced by the German battalions in squares, fully prepared to receive them. However, there was just enough room between the kitchen garden of La Haye Sainte and the allied infantry lining the ridge for the Cuirassiers to ride through and strike Kempt’s troops in their flank whilst they were fully occupied fighting with Bourgeois’ column. The Cuirassiers put spurs to their horses and actually managed to get their steeds into a slow trot as they swept elements of 1st Light K.G.L. and the 95th Rifles away.

Further to the right, Donzelot’s Division had also marched across the shallow valley under intense fire from infantry and a flanking fire from the artillery lining the crest. The column approached the crest line and saw with elation that some of the Dutch/Belgian infantry were breaking and they cheered as they saw victory within their grasp. But this time many of the infantry of Bijlandt’s left wing initially stood and poured in a steady volley and then attempted to advance to a bayonet charge. However, the grim determination shown by the head of the French column caused Bijlandt’s men to falter in their charge and then turn to flee, before actually coming to blows. Some fled all the way to the rear, but a number ran behind Pack’s Brigade and were reformed by their officers, but they offered very little more in the way of opposition; their will had been broken.

As with Bourgeois’ attack, the column reached the hedge lined trackway which ran along the crest, only to be struck by a heavy fire from both the 28th Foot which formed the left of Kempt’s Brigade and from the 1st Foot which was on the right of Pack’s Brigade. The first ranks of Donzelot’s column were decimated, but this time the sheer weight of numbers in this column drove it on and over those that fell.

The column of Marcognet’s Division had steadily drawn closer to the right of Donzelot’s Division as they moved up the allied slope and arrived just after them at the crest. This column arrived to find themselves in front of the 1st and 42nd, formed in line, who poured in a destructive volley and attempted to push them back with a bayonet charge. However, despite the damaging effect that their stout defence had upon the leading element of the column, sheer weight of numbers again told and Pack’s men were forced to slowly retire as they continued their valiant struggle to prevent the French succeeding. Sir

Denis Pack rode up to the 92nd on the left of the brigade which had not advanced with the others, shouting ‘Ninety Second, you must charge! All the troops in your front have given way!’ With a volley and a cheer the 92nd charged with the sound of bagpipes ringing in their ears. There is no doubt that their gallant charge did stall the advance of the column, but they could not hope to stem the flow, being only four hundred men against ten times that number.

At this moment, success for d’Erlon’s troops seemed almost inevitable, the crest was virtually theirs as the thin line of British defenders would soon inevitably be overwhelmed. The cheers of elation, for Victory and for their Emperor rose to a crescendo only to change in an instant to those of shock and fear as the shrill cry rang out ‘cavalry!’

The allied infantry on Wellington’s left wing were at crisis point, with d’Erlon’s much more numerous columns pushing intensely for a breakthrough – they were in dire need of support. It had become obvious to the Earl of Uxbridge that the infantry were going to struggle against such a formidable attack and he had prepared his cavalry, which lay in a hollow either side of the chaussee just a few hundred yards back behind the infantry. Lord Edward Somerset’s brigade of Household cavalry, numbering some one thousand men, consisting of two squadrons each of the 1st & 2nd Life Guards, the Horse Guards and the 1st or King’s Dragoon Guards were to the right of the chaussee and to the left stood Sir William Ponsonby’s ‘Union’ – English, Scottish and Irish – Brigade of over one thousand seven hundred superb horsemen of the 1st (Royal) Dragoons, 2nd Royal North British Dragoons (or Scots Greys) and the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons. The cavalrymen tightened their horses’ girths and then mounted, placed their heavy and uncomfortable helmets upon their heads and made sure that all of their equipment was secured; formed into line, drew their huge swords and many probably gave up a short prayer as they silently waited for the bugle to sound the advance.

The moment had arrived and the shrill notes of the bugle announced the ‘trot’, the two thousand five hundred men of the two brigades, heavily armed and on huge horses advanced at medium pace; the French infantry out of view were blissfully unaware of their existence just below the ridge line.

Suddenly the ground began to rumble as the horses cantered up the slope; the allied infantry were ordered to make way for them and they rushed to move apart to allow them through, not always quickly enough. As they passed through and round the British infantry and guns, to the French they appeared as if from nowhere only seconds before they actually struck home, giving no time for an organised response.

The right of the Household brigade advanced to the front, passing through the German troops in squares, quickly negotiating their way across the sunken way, and driving hard into the flank of Dubois’ Cuirassiers. The 1st Life Guards on the right of the line and most of the 1st Dragoon Guards swept straight down on Dubois’ disordered Cuirassiers, – which had just scattered the Luneburg Battalion to the four winds – and they appear to have been more than a match for them. Although protected by body armour the Cuirassiers proved vulnerable in the head, neck and limbs; and when in very close combat, where the Cuirassier could not easily strike with his stabbing sword, a hilt thrust hard into the face apparently did just as well! Soon the Cuirassiers were fleeing down the ridge along the western side of La Haye Sainte, with the Dragoon Guards and 1st Life Guards in hot pursuit and with the Blues following up as a reserve.

Whilst charging Dubois’ Cuirassiers the left wing of the 1st Dragoon Guards and the entire contingent of the 2nd Lifeguards veered to the left against the head of the Cuirassiers who were attacking the 95th near the crossroads; they drove the Cuirassiers away from them and pursued them down the eastern side of La Haye Sainte, where a number of the French got entangled with the abatis on the chaussee. The British cavalry rode on, meeting great crowds of fleeing infantrymen, which they scythed down like the heads of wheat as they charged down the slope.

The Union Brigade rode forward in line with no reserve to charge the infantry columns. French warning cries of ‘Cavalry’ seem to have caused a complete panic in the ranks of the columns as some men tried to form square but were not really sure how to do it in such an unfamiliar formation, others tried to open fire and many others panicked and simply ran from the rear of the column;but most simply found themselves hemmed in, packed too densely to move or offer serious resistance to the approaching cavalry. In all of the confusion many men deep in the column knew nothing of the cavalry until they or a neighbouring friend were struck down by the unforgiving swordsmen.

The 1st Dragoons rode straight ahead through gaps made by Kempt’s troops and struck what appears to have been the already retreating column of Bougeois, which then completely dispersed under the shock of the cavalry charge. As the Royals drove deep into the disorganised mass, Captain Alexander Clark saw a French officer carrying the Imperial Eagle of the 105th Ligne and forced his way towards him. Having stabbed him just above the kidneys with his sword, the eagle was dropped. Fortuitously however it fell against the necks of their horses as Clark shouted out ‘Secure the Colour! Secure the Colour!’ when Corporal Stiles caught hold of it and was ordered to carry it to safety in the rear.

The allied cavalry became engaged in a blood lust, their horses simply crashing through the packed ranks, some biting rabidly, as each horseman hacked to right and left as hard and as fast as they could until their arms ached with the effort and yet still they cut away. Wielded expertly by the Dragoons, the heavy cavalry sword slashed through everything, heads and arms were cleaved in two, the only possible escape was to lie down and feign death. Their blood was up and even mild mannered troopers showed a scant regard for those that cried for mercy or attempted to surrender; they just drove on and on into the dense crowd dispensing death as if they were gluttons for the gore. There was no time for prisoners.

To the left of the Royals, the Inniskillings drove through the gap between Kempt’s and Pack’s Brigades and struck Donzelot’s column head on, which had just reached the roadway. Again the cavalrymen drove into the heart of the column and it rapidly disintegrated and fled back down the slope.

And then the left hand regiment, the Scots Greys, rode round and through the 92nd Foot, to appear suddenly at full speed as they struck the ranks of Marcognet’s column. Second Lieutenant Jacques Martin described the confusion of the moment when the Greys struck.

We too in the mayhem of a confused and agitated crowd, shot many of our own people with shots aimed at the enemy. All bravery was useless… in vain our soldiers rose on their feet and stretched their arms out to try to stab with bayonets at the cavalry mounted on the tall vigorous horses. Useless courage, their hands and arms fell together to the ground and left them defenceless against a persistent enemy who sabred without pity even the children who served as drummers and fifers in the regiment, who asked in vain for mercy. It was there that I saw death closest. My best friends fell at my side, I could not believe that the same fate did not await me, but I had no more distinct thoughts. I fought like a machine, awaiting the fatal blow. I did not even notice the danger, or maybe it was providence that made the blows aimed at me fall aside, and until that moment I was without serious injury.

Martin was struck down by a horse and laid as if dead until he had an opportunity to run safely back to his own lines, exhausted, but alive.

swords streaming in blood, waving over their heads and descending in deadly vengeance. Stroke follows stroke, like the turning of a flail in the hand of a dexterous thresher; the living stream gushes red from the ghastly wound, spouts in the victor’s face, and stains him with brains and blood. There the piercing shrieks and dying groans; here the loud cheering of an exulting army, animating the slayers to deeds of signal vengeance upon a daring foe. Such is the music of the field!

The Scots Greys drove into the column with the pipes of the 92nd urging them on and their cries of ‘no quarter’ ringing in their ears. As they hacked their way through, Sergeant Ewart was covering his youthful officer, Cornet Kinchant, when he was shot down from behind by a French officer who had been spared by Kinchant only moments earlier.

Ewart on reaching the enemy, immediately singled out a French officer, whom, from being a very expert swordsman, he soon disarmed & was on the point of cutting him down, when Mr Kinchant on hearing the officer crying out ‘Ah mercy, mercy Angleterre’ said ‘Sergeant Ewart spare his life & let us take him prisoner’; Ewart considering that moment as a period for slaughter & destruction & not the proper time for taking prisoners replied ‘As it is your wish sir, it shall be done’ & dropped his sabre. Mr Kinchant to whom the French officer had delivered up his sword, addressed him in French, ordered him to move to the rear. Ewart was preparing to proceed in the charge when he heard the report of a pistol behind him & turning round from a suspicion of some treachery; the first object which met his eyes was Mr Kinchant falling backwards over his horse apparently in a lifeless state & the French officer attempting to hide his pistol under his coat. Indignant at such a dastardly act Ewart instantly wheeled round & was again entreated by this villain for mercy in the same supplicating terms as before, the only answer to which he returned was ‘Ask mercy of God for the devil a bit will ye get at my hands’ & with one stroke of his sabre severed his head from his body, leaving it a lifeless trunk on the field.

Ewart rejoined the charge and soon found himself near the Eagle bearer of the 45th Ligne Regiment which he succeeded in capturing.

The officer who carried it and I had a short contest for it; he thrust for my groin, I parried it off and cut him through the head; in a short time after whilst contriving how to carry the eagle (by folding the flag round my bridle arm and dragging the pole on the ground) and follow my regiment I heard a Lancer coming behind me; I wheeled round to face him and in the act of doing so he threw his lance at me which I threw off to my right with my sword and cut him from the chin upwards through the teeth. His lance merely grazed the skin on my right side which bled a good deal but was well very soon. I was next attacked by a foot soldier who after firing at me, charged me with the bayonet; I parried it and cut him down through the head; this finished the contest for the eagle which I was ordered by General Ponsonby to carry to the rear.

Having seen all three columns largely disintegrate, the British heavy cavalry swept down the ridge in pursuit of the great masses of disorganised infantry, cutting down all who failed to drop to the ground and feign death. Vandeleur’s Brigade moved forward without orders to act as a reserve but the 12th Light Dragoons commanded by Lieutenant Colonel the honourable Frederick Ponsonby became caught up in the advance and led his men into the melee but was severely wounded and remained upon the field near the French front line all night. The remainder of Vandeleur’s Brigade consisting of the 11th and 16th Light Dragoons, although coming to blows with the Lancers, did maintain control and attempted to form a reserve for the Union Brigade to retire upon.

Durutte’s Division and some regiments in the rear of the columns did form squares to fend off their attackers, then retired slowly to safety; the cavalrymen preferring the easier targets of the fleeing throng. Soon the cavalry reached the cannon on the forward ridge, which had been unable to open fire for fear of destroying great numbers of their own men. The heavy cavalry sought ever more sacrifices to their bloodlust, lightly armed gunners and youthful limber team drivers were not spared, no mercy, no quarter still prevailed.

The British infantry and as many as four hundred of Bijlandt’s brigade who had rallied, followed the cavalry down the slope and hastily rounded up nearly two thousand stunned French infantrymen and a number of standards, which they quickly marched off to the rear. Some of the cavalry were ordered to escort these prisoners to Brussels where they arrived that evening, initially causing mass panic within the civilian populace who took them for the advance guard of a victorious French army.

Captain Whinyates’ Troop of horse artillery was also sent forward from the reserve held at Mont St Jean and apparently took up the position vacated by Bijleveld’s horse battery a few minutes before. Whinyates parked his cannon on the ridge and ordered detachments forward with ground rockets, which they lay down at the foot of the ridge and set off spluttering wildly in the general direction of the French lines, where unbeknownst to him, they caused great consternation, few of the French having faced such a fearsome weapon, with their erratic flight and their tails of fire which scared the life out of both men and horses.

The zenith of the great allied cavalry charge was upon them, euphoria drove the cavalry on and even the Duke of Wellington reportedly enjoyed the spectacle immensely. But too often in the Peninsula, British cavalry charges had shown great promise only to lead to disaster and this occasion was to follow the same old pattern.

The cavalry had charged with their leaders at the fore, where they either died or simply lost control of the situation. Uxbridge and his aides de camp joined the charge and Major General Sir William Ponsonby commanding the Union Brigade died by a single lance wound. Only the Household troops had retained a reserve on which to retire, so that when the inevitable French counter attack occurred, the British cavalry were slaughtered in their turn.

With their blood up the men of the ‘Union Brigade’ ignored the bugle calls to retire and continued to seek new victims, it was only when they suddenly became aware of the Lancers and Chasseurs of Jacquinot’s division filing into the valley in their rear, cutting off their escape, did they realise their perilous position and attempt to retire back to the safety of their own lines.

The Lancers had shown no mercy to the infantry at Quatre Bras and were not going to be any more merciful now. The Scots Greys and Inniskillings sought to force their way to safety, but found their tired horses could not outrun their opponents and the Lancers struck down every British cavalryman that they could catch with a quick jab of the lance. With their extended reach, neither lying in the mud seriously wounded or feigning death did not save them, as all received further lance thrusts to ensure that they really were dead. The Royals, who had advanced nearer to La Haye Sainte returned with relative ease, most of the Lancers being far too busy to their left.

Private Thomas Playford of the 2nd Life Guards, also describes the confusion of the fighting admirably as he rode back and fore without managing to actually cross swords with anybody!

I pursued; my progress was arrested by a hedge, and I looked over the fence, when I saw dreadful deeds taking place in a paddock a little to my right: my blood was hot and I went to a gap in the fence, but it was choked up with horses struggling in the agonies of death. I turned to my left and saw fearful carnage taking place on the main road to Brussels; but my recollection of what I saw is confused like a frightful dream. Under a hot impulse I hurried to the scene, but the fighting there soon ceased; and all I could do was to ride after some Cuirassiers whom, however contrived to escape. As I rode on I saw our soldiers destroying the men and horses of some French artillery. But in whatever direction I turned every Frenchman got out of my way, excepting one Cuirassier who fell completely into my power. He was unhorsed, his helmet was knocked off, and I raised my hand to cleave his skull; but at that moment compassion sprung up within me – I checked the blow and let the conquered Cuirassier escape with a wound on the side of his head.

Some of the Scots Greys and Inniskillings managed to evade the Lancers and many were saved by the advance of the 12th and 16th Dragoons who attacked the Lancers and then formed up again to cover their retreat.

The Household cavalry to the west of La Haye Sainte had become embroiled in a mass melee with Cuirassiers which caused great losses on both sides in the bitter contest.

However the Cuirassiers were reinforced and a few ad hoc groups of Lancers also joined in; two of the commanding officers, Lieutenant Colonel Ferrior of the 1st Life Guards and Lieutenant Colonel Fuller of the 1st Dragoon Guards were killed and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Robert Hill commanding the Blues was only saved by the brave actions of Trooper Tom Evans.

Eventually they were forced to retire having suffered great loss, the Blues and Ghigny’s Dutch/ Belgian light cavalry brigade covering their retreat.

It is also clear that Lobau’s Corps was initially moved to the right to protect the batteries which were threatened by the British cavalry. These troops formed squares in rear of the cannon allowing d’Erlon’s broken troops to slowly rally and reform behind them. But many such a fellow as Trooper Thomas Hasker of 1st King’s Dragoon Guards, found that being wounded was only the beginning of his troubles.

…in crossing a bad hollow piece of ground, my horse fell, and before I had well got upon my feet, another of the French Dragoons came up, and (sans ceremonie) began to cut at my head, knocked off my helmet, and inflicted several wounds on my head and face. Looking up at him, I saw him in the act of striking another blow at my head, and instantly held up my right hand to protect it, when he cut off my little finger and halfway through the rest. I then threw myself on the ground, with my face downward. One of the Lancers rode by, and stabbed me in the back with his lance. I then turned, and lay with my face upwards, and a foot soldier stabbed me with his sword as he walked by. Immediately after, another, with his firelock and bayonet, gave me a terrible plunge, and while doing it with all his might, exclaimed, ‘Sacre nom de Dieu!’ No doubt that would have been the finishing stroke, had not the point of the bayonet caught one of the brass eyes of my coat; the coat being fastened with hooks and eyes, and prevented its entrance. There I lay, as comfortably as circumstances would allow, the balls of the British army falling around me, one of which dropped at my feet, and covered me with dirt; so that, what with blood, dirt, and one thing and another. I passed very well for a dead man.

Eventually the cavalry passed beyond the protection of British infantry formed in small rallying squares of 30 men or so upon the allied slope and all retired to the ridge line again, driving any last French prisoners back with them. The infantry took up their previous positions and the heavy cavalry now numbering less than half of their original numbers, retired to a hollow in the rear to reform and reorganise.

An uneasy period of relative peace descended upon this wing as both allied and French troops sought to reorganise themselves and catch their breath. Both were only acutely aware that the shallow valley was simply carpeted by their dead and dying comrades and none were too keen to immediately renew the carnage. For more than hour there was little more than skirmishing fire and an odd cannon shot.

The shattered remnants of all of the heavy cavalry including the Union Brigade were then moved to the right of the chaussee behind Alten’s Brigade.

Continue to the French Cavalry Charges